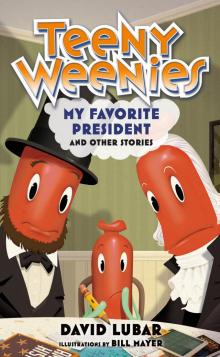

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President

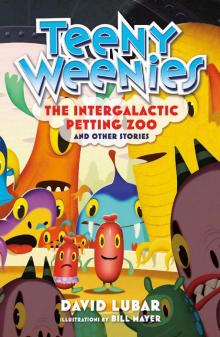

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo

Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus

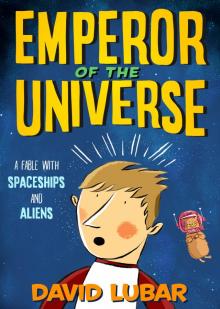

Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus Emperor of the Universe

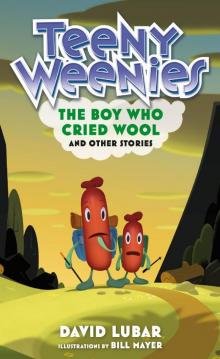

Emperor of the Universe Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool

Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets

Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy

Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy Numbed!

Numbed! Punished!

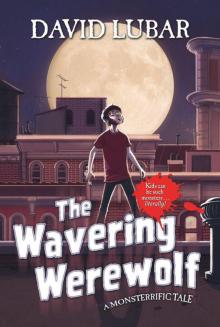

Punished! The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales)

The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales) Dog Days

Dog Days Sophomores and Other Oxymorons

Sophomores and Other Oxymorons The Psychozone

The Psychozone My Rotten Life

My Rotten Life Invasion of the Road Weenies

Invasion of the Road Weenies In the Land of the Lawn Weenies

In the Land of the Lawn Weenies Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies

Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies Ghost Attack

Ghost Attack Check Out the Library Weenies

Check Out the Library Weenies Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book)

Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book) Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories

Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories Hyde and Shriek

Hyde and Shriek The Wavering Werewolf

The Wavering Werewolf Dead Guy Spy

Dead Guy Spy Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies

Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies The Big Stink

The Big Stink The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies

The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies Character, Driven

Character, Driven The Bully Bug

The Bully Bug Beware the Ninja Weenies

Beware the Ninja Weenies Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge

Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge The Unwilling Witch

The Unwilling Witch Goop Soup

Goop Soup Lay-ups and Long Shots

Lay-ups and Long Shots The Gloomy Ghost

The Gloomy Ghost Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie

Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories

Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories Attack of the Vampire Weenies

Attack of the Vampire Weenies Enter the Zombie

Enter the Zombie The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale

The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale The Curse of the Campfire Weenies

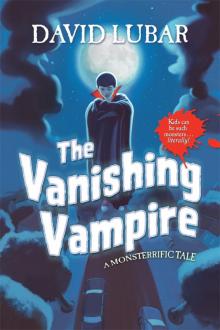

The Curse of the Campfire Weenies The Vanishing Vampire

The Vanishing Vampire