- Home

- David Lubar

Emperor of the Universe Page 14

Emperor of the Universe Read online

Page 14

“Menmar and Zefinora are no more your fault than this is mine,” Clave said. “I want you to die with a clear conscience.”

“Thanks.” Nicholas swallowed. I’m not ready for this, he thought. But he realized Clave had a point. He still felt guilty, though not as much as before. And not for much longer, he imagined. He put one hand on his pocket and stooped down to put his other hand on Jeef.

“Good-bye.”

Henrietta nuzzled his thumb.

Jeef bumped the cart against Nicholas’s ankle as gently as she could.

Marrow grabbed his collar. “Stand straight. This is an honor.”

Nicholas stood. The pressure on his back grew greater. It was time to either fall or jump. Neither option had any strong points in its favor. At least, if he jumped, he was taking control of his destiny. Maybe he could leap high, spin in the air, and spit in Marrow’s eye before he plunged to his death.

A shadow fell across them.

Nicholas looked up. Clave’s ship swooped down from the sky. It stopped right above the atomizer. A compartment opened in the bottom. Nicholas blinked against the glare as sunlight reflected off the falling cargo. Gold. Someone—it had to be Spott—was dumping tons of gold into the atomizer.

Nicholas hoped it would jam the blades.

It did far more than that. A screech tore through the air.

“No!” Marrow howled. He dropped his hand from Nicholas’s collar and stepped closer to the edge, reaching out as if he could snatch away the gold. A piece the size of a softball batted off a blade and struck him in the head. He staggered. One of his forelegs slipped from the edge.

Nicholas and Clave both pushed him hard. Marrow fell into the atomizer. The platform and the stairs beneath them started to shake. Horrible ripping sounds of tearing metal rose from the atomizer. Pieces of gold shot into the air as if smacked by a home-run champ. The ship drifted lower. The hatch opened, just a few feet away from Nicholas. Sharp cracks of breaking wood tore the air as the stairs began to splinter from the quake, tossing aside Zeng pilgrims like drops of water flung from a wet dog.

Spott stood at the edge of the ramp, one arm wrapped around a handhold, the other arm extended. “Jump!”

Nicholas held on to Henrietta and jumped. Clave followed him.

“Wait!” Nicholas looked back at the platform, which was now tilted toward the abyss. Jeef tottered there, her wheels spinning and smoking against the wood as she fought to keep from sliding to her death. And once again, Nicholas went back to rescue her.

I knew you’d come, Jeef said.

“Catch,” Nicholas shouted, tossing the cart to Clave as the platform lurched beneath his feet. Nicholas jumped back into the ship just as the stairs collapsed.

“I don’t know whether to kill you or hug you,” Clave said to Spott.

“How did you know this was going to happen?” Nicholas asked as the hatch closed.

“I heard them discussing it,” Spott said.

“I didn’t hear anything,” Clave said.

I didn’t, either, Jeef said.

“Neither did I.” Nicholas thought back to their arrival at this strange and horrible place. “And I was right next to you when we left the ship. What about you, Henrietta?”

“Nothing,” she said.

“How about the truth?” Nicholas said.

“I can sort of read minds,” Spott said.

“Sort of?” Nicholas asked. He thought about when Spott had scratched him, and when Spott had tricked them. The words that could have been plucked from his mind at those times were not very complimentary.

“More than sort of, I guess,” Spott said. “We all can, where I come from. And we know how to shield ourselves. We usually don’t talk about it, because it bothers some aliens. Others don’t care at all. And there are some, like the Yoranit, who derive deep pleasure from knowing that others have heard their thoughts. The main thing is I knew what the Zeng were planning the instant I got close to them. Grabbing the ship seemed like the best way to get you out of there alive. Don’t worry—I repaired the hull.”

“And you knew how to pilot it?” Clave asked.

“I pulled that from your mind while we were traveling,” Spott said. “It’s really almost trivial. A child could do it, actually. Even a two-year-old.”

Ooohhhh. I’m two. Can I fly? Please, let me fly, Jeef said. She rolled back and forth like an impatient toddler bouncing from foot to foot.

“It is not easy,” Clave said. “It takes years of practice.”

“Guys,” Nicholas said, pointing to the viewport, “maybe you can talk about this later. How about one of you gets us away from here before we get gold plated or ground to pieces.”

Outside, the mountain was shaking violently, spewing gouts of flame and splashes of molten gold. Hunks of the rim broke off and plunged into the opening or rolled down the slope.

Clave dove past Spott to claim the control seat. “This is a job for a real pilot.”

“Wait!” Nicholas cried. He dropped to his knees, then fell to his face. As acceleration pinned him to the floor, he looked over at Spott, who was also splayed out, and asked, “Did you drop all the gold?”

“I think so. Dreadful stuff. But I guess we were lucky it was in the cargo hold. It seems to have put a stop to this device.”

“I think it did more than that,” Nicholas said when he was able to get up and check the viewport. Below them—now safely far below—the mountain appeared to have collapsed on itself, leaving an enormous opening in the ground. That wasn’t the end of the destruction. More ground was pulled into the opening, as if the planet was devouring itself.

Which was exactly what it was doing.

SICK-TEMPERED TYRANT

Speaking of mortality, the Emperor of the Universe was dying.

For the 178th time.

His Hugeness Zrilber Monospokodokapusimus (“Zril” to his friends, of which there weren’t many since he had a habit of killing them for fun when he got bored) could feel his body rotting from the inside out. That was a problem, but it was not yet a crisis. All he needed to pull himself back from the edge of death was a crowd. An enormous crowd.

A miniscule percentage of Theribans can draw vitality from others. Perhaps one in every five million are born with this trait. This is a well-kept secret among those Theribans, since the vitality they draw is subtracted from the lives of their unknowing donors.

Those Theribans had also learned, centuries ago, to draw what they needed from a crowd, so as not to attract a crowd. Otherwise, suspicion would grow as people died or fell ill in the presence of dying Theribans who miraculously got well and sprang from their death trench, all cheerful and chipper, just brimming with good health.

The emperor, of course, could capture a planet and suck the vitality of the captives. But history had showed that warring emperors lived far shorter lives, whether capable of revitalization or not, than peaceful, or seemingly peaceful rulers. Zril had studied the history of many of his predecessors. You can fit in a lot of studying in 178 lifetimes, and still have plenty of time left for partying and watching episodes of Let’s Cut Things Up!

In one of those annoying catches the universe seems so fond of, each resurrection required a larger mass of vitality donors. Zril had recently paid a visit to one of the emigration centers being used for the evacuation of Plenax IV. But he’d gone toward the tail end of the rescue efforts. The crowd was large enough to stabilize his decline for the moment, but nowhere near large enough to reverse the decline and remove him from the endangered-emperor list.

Zril needed an entire planet densely packed with living beings. Unfortunately, the ease with which people could travel to other worlds had put a serious dent in the availability of densely packed civilizations. There was only one place he was aware of where he could find what he desperately needed quickly enough to revive himself. It was also a place he could visit without causing any suspicion.

“I will be attending this,” Zril said, indicati

ng an invitation to the Xroxlotl concert, which was to be held on one of the largest stadium planets in the universe. Traditionally, every major event extends an invitation to the emperor. It is a great honor if they attend, and a great relief if they don’t.

“Very well, Your Hugeness,” his retainer, Pumplock, had said. “I will make the arrangements.”

Pumplock did an excellent job of hiding his dismay. Traveling with the emperor was an enormous and unpleasant task, involving multiple ships and dozens of staff. Pumplock knew it would be a nightmare. Though, as a longtime fan of the group, he’d have died for a chance to hear Xroxlotl.

ONWARD

Now that the ship was safely away from the self-destroying planet, Clave got up from his seat. “You didn’t happen to secure the rest of the cargo, did you?”

“I didn’t know there was anything else,” Spott said. “I just got bombarded by a constant stream of thoughts about the gold, fast cars, attractive actresses, and algebra. I found it strange that math education involved dancing slowly with one’s instructor. Eventually, I screened it all out.”

“Oops,” Nicholas said. “I guess that was me.”

Clave opened the hatch and moved down the steps. “All gone,” he said. “The straps broke. I guess I’m not delivering those pet Orbanies.” He came up the steps, then dropped back into his seat. His body started to tremble. “Poor Orbanies … Innocent little creatures…”

“What’s wrong?” Nicholas asked. He wasn’t sure whether trembling meant the same with Menmarians as with humans.

It did. As did the reactions that followed.

Clave shook his head, then let out a wail.

“Clave?” Nicholas asked. “What’s wrong?” He’d never seen Clave exhibit much feeling or emotion, other than outrage and envy.

“The globes. The two of them. Dead. Gone,” Clave said. “Beautiful Orbanies. They were so full of life. So beautiful.”

Spott stepped toward Clave, but Nicholas put a hand on Spott’s shoulder and whispered, “Let him be. He needs time.”

He led Spott out of the cabin, into the corridor.

“His mind was too jumbled to read clearly,” Spott said. “It was full of death and sorrow. The weight was unimaginable and unbearable. It’s not about those fish.”

“Right. It’s not about some silly pets,” Nicholas said.

“Hey!” Henrietta said. “Pets aren’t silly.”

“Sorry,” Nicholas said. “I didn’t mean you. I never think of you as a pet. You’re a companion. And a wonderful one.” He flinched as he realized he sounded like a parent trying to stroke a child’s bruised ego.

What am I? Jeef asked.

“Lunch,” Henrietta said.

At least I have a purpose, Jeef said. I don’t just run around, chew things, and poop in people’s pockets.

“Stop it,” Nicholas said, though he couldn’t help smiling when it hit him that poop in people’s pockets could be part of a pretty funny tongue twister. “You’re both important. Now just be quiet for a moment.” He told Spott about Menmar, and the destruction of the binary planets.

“None of that is Clave’s fault,” Spott said. “Or yours.”

“But it’s his loss,” Nicholas said. “It took him a while to absorb the reality of it, I guess. Everyone he knew is gone. And everything. I’m not sure I’ve absorbed it, myself. And now, this.” He tilted his head in the direction of Zeng.

“Again, not your fault,” Spott said. “I get the blame for this one.”

“You saved us from a pretty horrible fate,” Nicholas said. “Look. Let’s just not talk about blame or anything for a while. Deal?” He held out his hand.

Spott stared at it. “Why are you offering to clean out my ear wax?”

Nicholas jerked his hand back. “It means something different on Earth.”

“I know. I was kidding you.” Spott held his own hand out. They shook. “Deal,” he said. He reached out toward Nicholas’s ears, but caught himself before he extracted any wax. Lifelong habits are difficult to break.

After that, they sat on the floor and waited, and exchanged basic biographies. Spott picked up a lot of the details from Nicholas’s thoughts, but Beradaxians were skilled at letting others speak, even when they knew what they were about to hear.

Eventually, Clave poked his head into the corridor. “Ready to hit the road?”

“Sure,” Nicholas said. Clave sounded a bit too cheerful, but Nicholas could tell he was feeling better. “I could definitely use a day or two where nothing exciting happens.”

“Road?” Spott asked.

“Earth saying,” Clave said. “Pretty catchy. For a barbarian planet, they come up with some clever expressions and inventions. It’s a very amusing place to visit. If you pile up a group of boulders or slabs of rock in an interesting way, the natives will flock there for centuries to stare at it. It’s also great fun to scoop up a couple hundred frogs from one place and put them in another. But enough of that. We need to decide what we’re doing.”

Nicholas and Spott spoke simultaneously: “I want to go home.”

“Where’s home?” Clave asked Spott.

“Beradaxia,” Spott said. “In the Crab Nebula.”

Clave checked the navigation computer. “We can’t get there. Not enough j-cubes. No cargo to deliver. And I can’t get my fee for dumping the gold without proof I disposed of it properly. We’re going to have to find someplace where we can earn some money. Do you have any skills?”

“I can pilot a ship,” Spott said.

“Any skills we don’t already have very well covered by trained experts who’ve been doing them for years?” Clave asked. He reached into the navcom and set the ship in motion. “I’d like to see you fly in a perfect circle so smoothly.”

“I’m good with my hands. I like to make bread. I can program computers,” Spott said as the ship lurched into motion.

“The universe is oversaturated with bread and programmers,” Clave said. “Let’s make it a figure eight.”

“I’m never getting home,” Nicholas said, to nobody in particular. “Stupid j-cubes.”

As the ship lurched into motion in different directions twice more before lurching to a stop, Nicholas thought about the report on subway systems he’d written in fifth grade. It had been in the back of his mind ever since Henrietta had explained how she believed the jump nodes worked. While doing research for the report, Nicholas had learned there were places where two or more subway lines crossed. No line went everywhere, but people could go almost anywhere in some cities by changing to a different line at one of these transfer stations. They could even travel on multiple lines if they were willing to make multiple changes. But, sometimes, it was easier and quicker to switch train lines by leaving one train and walking a short distance to a different station.

“Hey, I have a question,” he said.

“That’s hardly a surprise,” Clave said.

“This is serious,” Nicholas said. “Are there any jump nodes that are close to other ones?”

“Sure,” Clave said. “That happens all the time. Why?”

“If I understand how this works, you jump from node to node, following a series of links to your destination. Right?”

“Basically,” Clave said. “Though the details are complicated.”

Nicholas ignored that, and explained his idea. “Let’s say you need to go somewhere, like Spott’s home planet, and it takes three jumps. Suppose you find a jump node that’s close to one you can jump to, and is also only one jump from your destination? You could get there in two jumps, right? You’d just have to do a bit of regular travel in between.”

Clave was staring at Nicholas, as if he wasn’t sure how to process a complex idea coming from a barbarian, but Spott smacked his own chest and said, “That’s brilliant!”

“Somebody must have thought of that already,” Nicholas said. “It seems pretty obvious.”

“Not necessarily,” Spott said. “People who use hyperj

umps think in terms of instant travel. And you can get from any jump node to any other, as long as you make enough jumps. So it’s not surprising nobody thought about traveling the old-fashioned way from one jump node to another, as part of a trip.”

“So, maybe we can get to your planet or mine with two jumps,” Nicholas said. “We just have to find the right path.”

“I don’t know how we can find something like that,” Clave said. “And I’m not getting stuck near Earth with no way to make another jump.”

“We can modify the navigation software to look for routes that include spaceflight between reasonably close jump nodes,” Spott said. He turned to Clave. “They have j-cubes back home on Beradaxia.”

“And we have no money,” Clave said.

“We’ll figure something out,” Spott said. “First, let’s see if we can get there. What’s your top sustainable acceleration?”

Clave told him. Spott took Clave’s place at the console, and pulled up an image that contained the subroutines of the navigation software. He talked to himself as he worked.

“All right. We have an origin node and a destination node. Check each node we can jump to from the origin—let’s call that origin plus one—check each origin-plus-one node for nearby nodes that can be reached within an acceptable travel time, maxtrav. Let’s call those adjacent nodes. No. Attainable nodes. That’s better.”

Nicholas realized Spott was thinking out loud as he modified the software. He was amused that he was, in a sense, now reading Spott’s mind. Not that what he heard made a lot of sense. Still, he enjoyed trying to follow the logic. It was interesting to see that the process involved lots of backtracking and refining. He’d always assumed everyone else was a lot more efficient at solving problems and thinking things through. Spott’s continuing monologue showed him otherwise.

“We can set a large acceptable maxtrav, initially. If we find nothing, we move on. If we get a hit, we loop and reduce maxtrav until there are zero adjacent nodes. That’ll guarantee finding the quickest route. Wait. That’s inefficient. Better to start with the closest node and move outward until we reach maxtrav. Next, check each adjacent node for number of jumps to the destination. Whichever uses the fewest jumps becomes the preferred route. If none of them save jumps, go to each origin-plus-one node and check them the same way, for each of the origin-plus-two nodes. Repeat until origin-plus-N, where N is equal to the number of jumps in the original path. And simultaneously run the same algorithm from the destination back to the origin, of course, since routes are reversible.”

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo

Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus

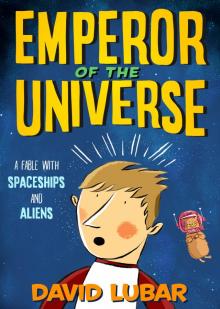

Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus Emperor of the Universe

Emperor of the Universe Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool

Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets

Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy

Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy Numbed!

Numbed! Punished!

Punished! The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales)

The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales) Dog Days

Dog Days Sophomores and Other Oxymorons

Sophomores and Other Oxymorons The Psychozone

The Psychozone My Rotten Life

My Rotten Life Invasion of the Road Weenies

Invasion of the Road Weenies In the Land of the Lawn Weenies

In the Land of the Lawn Weenies Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies

Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies Ghost Attack

Ghost Attack Check Out the Library Weenies

Check Out the Library Weenies Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book)

Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book) Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories

Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories Hyde and Shriek

Hyde and Shriek The Wavering Werewolf

The Wavering Werewolf Dead Guy Spy

Dead Guy Spy Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies

Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies The Big Stink

The Big Stink The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies

The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies Character, Driven

Character, Driven The Bully Bug

The Bully Bug Beware the Ninja Weenies

Beware the Ninja Weenies Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge

Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge The Unwilling Witch

The Unwilling Witch Goop Soup

Goop Soup Lay-ups and Long Shots

Lay-ups and Long Shots The Gloomy Ghost

The Gloomy Ghost Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie

Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories

Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories Attack of the Vampire Weenies

Attack of the Vampire Weenies Enter the Zombie

Enter the Zombie The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale

The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale The Curse of the Campfire Weenies

The Curse of the Campfire Weenies The Vanishing Vampire

The Vanishing Vampire