- Home

- David Lubar

The Bully Bug Page 2

The Bully Bug Read online

Page 2

“Ludlow Axelrod Mellon,” Mom said, calling me by my full name, which she only did when there was trouble, “where are your manners?”

“What, Mom?” I asked. It wasn’t me fighting at the table or wrestling across the floor.

“Use your fork, boy,” Dad said. “Always use the right tool for the job.”

I looked down at my hands. I’d been so busy watching Clem and Clyde fight that I guess I really hadn’t paid any attention to how I was eating. I’d grabbed a piece of meat with my hands. I guess I’d been biting at it. Yeah—there was a big chunk out of it, and I had the taste of meat in my mouth. Funny—I hadn’t even realized I was eating. We hadn’t even said grace yet.

“Cool,” Pit said. He dropped his action figure, grabbed a slab of beef with two hands, like he was playing a harmonica, and started chomping at it.

“Pitney,” Mom warned, hitting Pit with a full first name. That’s not as bad as getting a whole name—first, middle, and last—but it’s not good, either.

“Lud was doing it,” Pit said.

“If he jumped off a bridge, would you jump off, too?” Mom asked.

“Yup,” Pit said, nodding. “We Mellons stick together.”

Mom sighed and didn’t say anything more about manners.

After a while, Clem and Clyde came back to the table and joined us. I guess they’d gotten all tired out from fighting. They both grabbed the top burger again and it broke in half, which is the only way they ever settle anything. Funny how a squished-up half of a burger made each of them happier than a nice unsquished whole one.

Things quieted down for a little bit. We were too busy eating to talk or argue much. Then Dad hollered, leaped from the table, and dashed across the kitchen. He stomped his foot down hard enough to shake the walls and make Mom’s Wizard of Oz collector plates rattle where they were hanging, on the wall above the window. “Gotcha!” he shouted.

Dad hates bugs. He can spot an ant a mile away. He keeps a flyswatter in every single room in the house. He turned toward me. “Lud, get the spray.”

Why did it always have to be me? “How about Bud?” I asked.

“I’m eating,” Bud said through a mouthful of chicken and potatoes. I wasn’t going to argue. Not while Bud had his face stuffed. I didn’t want to get into a shouting match with him when his mouth was full—which it always was during dinner. I got up, climbed the steps to the second floor, then pulled down the ladder that led to the attic. Dad kept the spray in the attic because it was real dangerous stuff.

I hated it up there. It was dark and hot. And you had to be careful with the door. It was a trapdoor. And that was too true, because the handle on the inside had broken off. So if you let it close, you got trapped. Then you had to bang and wait for someone to come along and let you out. But at least the spray can was right next to the opening, so I could grab it without going inside. I could see where Dad had cut the first vent hole, at the edge of the floor where it meets the roof. But until he put in a fan, it would stay real hot, since the air didn’t move much.

Dad would probably let Bud help him put in the fan. Bud’s good with tools. Heck. Everyone in the family is good at something useful. Except me. Clem and Clyde are good at sports—especially wrestling. I guess because they get so much practice on each other. Mom can cook. Dad and Bud can fix things. May can sew. Pit draws like a real artist, even though he’s just five. Well, no use thinking about all the things I’m not good at. That would take way too long.

I brought the can to Dad. It was a big plastic tank with a pump on top and a long hose that had a nozzle on the end. Dad buys bug spray by the gallon. He pumped the handle a couple times, then sprayed along the floor near the window. “Getting low,” he said as he shook the can.

I finished eating, then helped clean up. Tomorrow was Thursday. I still had some homework to do. Actually, I had all my homework. It tends to pile up that way. I would have stayed in the kitchen for a while, but the smell of the spray was making me dizzy. It usually doesn’t do that. Until now, I’d kind of liked it.

Anyway, I went upstairs and got out my backpack. But I had a hard time that night. I mean, I always have a hard time, because a lot of the stuff they want us to do doesn’t make any sense. But tonight was hard in a different way. I was supposed to read all these pages in my history book, but my eyes kept getting funny, like I was looking through one of Mom’s fancy glasses—the bumpy ones we use on holidays.

“Forget it,” I said, tossing the book down on my bed. “I can’t do this.”

I looked across the room. Bud had already gone to sleep. We have to share a room. That’s pretty much okay, except Bud makes a ton of noise when he sleeps. He says I do, too. But I don’t believe him. Sometimes it sounds like he’s drowning in a bucket of maple syrup. Other times, it sounds like he’s trying to chew a mouthful of gravel. There’s no way I’d make that much noise. Hey—that’s an idea for a joke. When Bud’s asleep, he makes so much noise, you could say he’s sound asleep. Sound asleep. That’s a good one.

I slipped into bed. It wasn’t cold, but I pulled up the sheet and wrapped it tight around my body. It felt good, being all wrapped up.

I fell asleep just fine. Usually, I don’t wake up until May starts shouting. But it was still dark when I opened my eyes. “What’s going on?” I said out loud when I realized that I wasn’t in bed. No mattress under my body. No pillow under my head. No sheets. It didn’t make any sense.

Something was very wrong.

Four

HANG ON

“What’s going on?” I asked, talking quietly so I wouldn’t wake up Bud. I couldn’t even figure it out for a minute. There wasn’t a lot of light, just a quarter moon shining through the window. I had my hands pressed against something smooth and cool. It wasn’t the floor, because all the floors in the house were made of wood boards, and whatever I had my hands on didn’t feel like wood. But that wasn’t the strangest part.

Something was pulling at me.

Something was trying to lift me up from the floor. No, that wasn’t right, either. I wasn’t being pulled up. I was being pulled down.

Down?

I let my head flop back. I looked at my bed. It was under me. No way. That meant I was holding on to the ceiling.

I jerked hard and felt my hands and feet pull off the ceiling like it was covered with glue.

I dropped straight down and hit the bed. I didn’t make much noise when I smacked the mattress. But I made a huge crash when the mattress broke through the bed frame and hit the floor.

The whole house shook.

“Hey!” Bud shouted from his bed. “Quit making all that noise.”

“Sorry.” I was too flustered—that’s one of Mom’s favorite words—to argue with him. I pressed my hand against the wall, wondering whether it would stick.

Nope.

Just to make sure, I smacked my palm flat against the wall. It still didn’t stick. I smacked it harder.

“Will you stop that banging!” Bud shouted.

“Sorry.” I got back under the sheet and tried to figure out what had just happened. It had to be a dream. Yeah. That made sense. I’ll bet the bed broke, and I just dreamed the rest. It’s like that old joke about the kid who dreams he ate the world’s biggest marshmallow. Then he wakes up and his pillow is missing.

Must have been a dream.

I went back to sleep.

“Time for school! Get up, Lud!”

I hate it when May wakes me. I jumped out of bed. That turned out to be a mistake, since my mattress was flat on the floor. I tripped over the bed frame.

Talk about waking up on the wrong side of the bed. But things got better right away. Mom made waffles for breakfast. We all like waffles, especially Mom’s. She doesn’t even use a mix. She makes them from scratch. Breakfast is the most important meal of the morning. That’s what Dad always says.

After we ate, I headed off to school with Bud, Clem, Clyde, and Pit. We had to walk, since we’d gotten thrown

off the bus too many times and the school sent a letter saying we couldn’t ride anymore. That hardly seemed fair.

Clem and Clyde split off after a while, since they go to the middle school. Bud and Pit and I went on through town to Washington Irving Elementary. We walked Pit to the side door for his kindergarten class, then went around to the front.

“I hate this place,” Bud said when we walked up the steps into school.

“Yeah.” I didn’t like it, either. Everyone always stared at us, because they thought we weren’t as smart as them. And because we’re big. I’m taller than some of my teachers. And I guess they also stared because our dad doesn’t make a lot of money and because his car is old and all beat up, with one door that’s a different color. But there’s better things in life than being smart. And there’s better things than having money or a fancy car. That’s a fact.

“See you at lunch,” Bud said.

“See ya.” We had to split up. They’d put us in different classes. Bud had English first. I had math. I think they split us up on purpose because they don’t like us. None of my teachers do. Except maybe for Ms. Clevis. She’s nice. But mostly, teachers don’t like me. Especially Ms. Edderly. I had her for English, and she was flunking me. That wasn’t fair. I’d been speaking English all my life. It was like someone saying I’d flunked breathing or eating. It didn’t make sense. But that didn’t seem to make a difference to her. As I said, almost all my teachers didn’t like me.

Not that anyone else in the school does, either. I’m not complaining. I’ve got my brothers. That’s all I need. I had a girlfriend for a little while, but it didn’t work out. Dawn wanted to go for bike rides and picnics. No thanks.

Well, as Dad always says, It don’t do no good crying about the past when there’ll be plenty to cry about in the future. Especially since I was about to go to my first class of the day and I didn’t have my homework done.

I shoved my books into my locker and slammed the door. As I walked away, I bumped into something.

“Oooff.”

Oh no. It was that brainy little squirt. Nerdy Norman. I’d just knocked him flat. It wasn’t my fault he was standing there. He looked up at me with those terrified little eyes of his, like I’d done it on purpose. He reminded me so much of a beaver with glasses, I couldn’t help laughing.

I guess I should have told him I was sorry for knocking him down, but then he might start talking to me. Besides, he wasn’t hurt, so there really wasn’t anything to be sorry about. But I figured I’d better say something. “Watch where you’re walking next time,” I told him. I hadn’t meant to sound so mean, but that’s what came out.

He nodded. I turned away before he had a chance to say something I didn’t understand. I hate those brainy kids. They’re always showing off, using words like thermodynamics and metaphors, whatever that means. And they make fun of me more than anyone else. They love to say stuff I don’t get. I could show him a thing or two. I could say some real clever stuff. But what’s the use? I turned away from him and went down the hall.

“Another stupid day,” I muttered as I walked to my desk at the back of the classroom.

I’d just gotten comfortable—at least as comfortable as I could get in one of those small chairs—when they started the morning announcements. It was the same stupid stuff they always have, about teams winning games, and kids getting special awards. I didn’t pay any attention. Until the end.

Five

PLANE PROBLEMS WITH NUMBERS

“We won’t be having a play this spring,” Principal Wardener said over the loudspeaker. “Instead, we’re going to try something different. We’re going to have a talent show. I’d like to encourage everyone to try out.”

I closed my eyes for a minute when I heard that. I could see myself onstage, doing my jokes. Making everyone laugh. Telling my best jokes, just like the comedians on TV. But as soon as I had that picture in my mind, all the faces in the crowd turned mean. They laughed at me.

I slammed my fist against the desk.

“Lud, what are you doing?” Mr. Phermat, my math teacher, asked.

“Nothing,” I said.

“Well, stop pounding the furniture,” he told me, smiling like that was some kind of great joke. He wasn’t funny. He should have said something like Snap out of it, since if I hit the desk hard enough, I’d snap it. Now, that would be funny. At least, I thought it would be. Or he could have said something about how I’d gained a few pounds, since I was pounding the desk. Or he could have told me to take a break.

He went up front and started the lesson, but I couldn’t keep my mind on math. I kept thinking about the talent show. If I got up onstage and showed them how funny I was, people would treat me better. They’d be nice to me. But I couldn’t. There was no way I could get onstage in front of everyone. No way.

“Well, Lud, can you answer the problem?”

Oh no. I looked up at Mr. Phermat. He’d been talking to me. And there was a problem written on the chalkboard. It was one of those stupid distance things, where a couple planes are flying in different directions at different times. I hated those. I just didn’t get how to do them. Heck. Almost nobody could figure them out, anyhow. Except for the real smart kids.

Mr. Phermat stared at me for a moment. I knew that he knew I didn’t have a clue. So it was pretty mean of him to even ask me. I opened my mouth to say, I don’t know. If I had a nickel for every time I’d said those three words, I’d be rich.

But this time, I didn’t say it. There was something about the problem.… I stared at the board. I’d always figured stuff like that was about numbers and math. But I realized that it was really about flying. Everything got real clear. If the first plane took off at eight, like they said, and the second one was flying twice as fast and took off two hours later, then …

“They cross at two fifty-eight,” I said.

Mr. Phermat started to turn away from me. Then he spun back and dropped the chalk. For a minute, he stared at me. When he was done staring, he glared around at the rest of the kids. “All right, who whispered the answer to him? Did you, Norman?”

“What?” Norman the Nerd shouted, like he’d been accused of murdering the class guinea pig. “I’d never do that. Honest. You know I’m psychologically incapable of such egregious and subversive behavior under any circumstances, especially in a pedagogical environment—”

“Okay.” Mr. Phermat turned away from Norman and started writing another problem on the board. Go figure. All year, he’s been angry because I didn’t understand anything he was teaching. When I finally gave an answer, he got even angrier. As Dad always said, The only way you can please some people is to make them unhappy. You got that right.

On top of all that, I didn’t have a clue where the answer came from. I looked around the room. Maybe someone had whispered it to me. No. Most of the seats near me were empty, except for the one Toby Meyers sat in over to my left. He pretty much slept through class, so he didn’t care who he was next to.

“All right, smart boy, try this one,” Mr. Phermat said. He pointed to another problem on the board.

Airplanes again. Flying all over the place. “Two hundred miles an hour,” I said, not giving it much thought.

Mr. Phermat glared around the room again. He wrote another problem on the board. This time it was just division. But a long one. With decimals, too.

“Do it,” he said, tossing me the chalk.

“I can’t…,” I said.

“Do it!”

I walked up to the board and stood there, looking at the numbers, trying to remember how to figure out division.

Behind me, they were all starting to laugh. When I heard the giggles, my brain shut down completely. I wanted to put my fist right through the board.

“What’s the answer?” Mr. Phermat shouted.

“I don’t know!” I shouted back.

“That’s enough,” Mr. Phermat said. “Take your seat. Whatever kind of trick you were pulling, I think we just put

a stop to it with some simple math.”

Yeah—it was enough. I tossed the chalk away and walked to my seat. Go ahead, I thought as I stomped past the nerd. Laugh, you stupid smart kid. I really wished he’d laugh. Then I’d give him something to cry about.

He turned away from me and start flipping through his math book, like he had something important to look up. I could tell he was scared. Good.

I glared at the board. I had no idea how I’d answered those stupid problems. It had to be a lucky guess. Not that it mattered. I wasn’t good with numbers. That’s a fact.

At least the bell rang soon after that. I gave Toby a push and said, “Wake up.”

Then I headed for my next class.

“Hey, Lud,” Bud called, running down the hall toward me.

I waited for him.

“Guess what?” he asked when he reached me.

“What?”

He grinned. “This is great. Wait till you hear what I did. It’s probably the biggest favor anyone’s ever done for you. But that’s what brothers are for.”

“What?” I asked again. I knew it would take a while to find out.

He told me how great the surprise was a couple more times, then how wonderful he was, and then just when I was about ready to scream, said, “I signed you up.”

“For what?”

“The talent show,” he said, grinning an even bigger grin so his mouth looked like a piano. “You’re all signed up. Better start practicing.”

Six

A BAD SIGN

“Are you crazy?” I asked Bud. “No way I’d do that stupid show.”

“You have to,” Bud said.

“Why?” I couldn’t see any reason to get up on a stage in front of a whole bunch of people who didn’t like me and try to make them laugh.

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo

Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus

Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus Emperor of the Universe

Emperor of the Universe Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool

Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets

Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy

Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy Numbed!

Numbed! Punished!

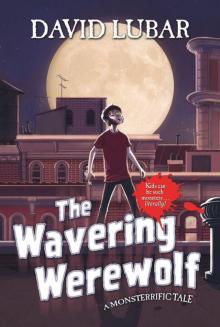

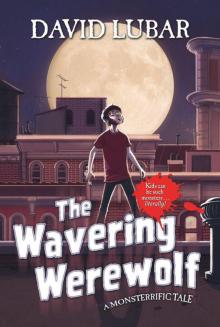

Punished! The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales)

The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales) Dog Days

Dog Days Sophomores and Other Oxymorons

Sophomores and Other Oxymorons The Psychozone

The Psychozone My Rotten Life

My Rotten Life Invasion of the Road Weenies

Invasion of the Road Weenies In the Land of the Lawn Weenies

In the Land of the Lawn Weenies Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies

Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies Ghost Attack

Ghost Attack Check Out the Library Weenies

Check Out the Library Weenies Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book)

Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book) Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories

Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories Hyde and Shriek

Hyde and Shriek The Wavering Werewolf

The Wavering Werewolf Dead Guy Spy

Dead Guy Spy Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies

Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies The Big Stink

The Big Stink The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies

The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies Character, Driven

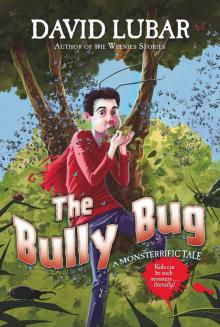

Character, Driven The Bully Bug

The Bully Bug Beware the Ninja Weenies

Beware the Ninja Weenies Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge

Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge The Unwilling Witch

The Unwilling Witch Goop Soup

Goop Soup Lay-ups and Long Shots

Lay-ups and Long Shots The Gloomy Ghost

The Gloomy Ghost Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie

Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories

Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories Attack of the Vampire Weenies

Attack of the Vampire Weenies Enter the Zombie

Enter the Zombie The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale

The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale The Curse of the Campfire Weenies

The Curse of the Campfire Weenies The Vanishing Vampire

The Vanishing Vampire