- Home

- David Lubar

The Wavering Werewolf Page 2

The Wavering Werewolf Read online

Page 2

Outside my window, I could see a squirrel running down the tree by the side of the driveway.

I started doing the homework problems. The first question involved two jet planes moving at different speeds.

The squirrel left the trunk and crawled onto a large branch. It looked around, then moved carefully toward the middle of the branch.

I calculated the distance covered by the first plane. It was simple: Distance equals speed multiplied by time. There was a rattling wooden clack as the pencil slipped from my fingers and hit the desk. I stood and walked, slowly, silently, toward the window. My feet met the floor with less than a whisper.

The squirrel, ten feet away from the house, swished its tail and took another step.

Carefully, I slid the window open and removed the screen. I had not yet made the slightest sound other than a faint scraping as the screen slid free. My mind flicked to the next part of the problem. The second plane had gone half the distance of the first, so the answer was obvious.

The squirrel sensed something. It looked toward me. Its body tensed, preparing for a dash to safety. The tail lifted and twitched.

Where was my pencil? I should write down the answer.

The squirrel turned its head. Our eyes met. I held the creature as our gazes locked. For a moment, it froze. But its need to survive was strong. The squirrel broke from the grip of my stare. I knew it would run back toward the trunk in an instant. I had to make my move now, or I would lose the chance.

I leaped.

Four

HANGING OUT

I suspect my lack of athletic ability saved my neck. If I’d had any coordination at all, the leap would have carried me right out the window. There’s no way I could have reached the tree. Even the greatest athlete in the world couldn’t have made that jump. Luckily, I’m a bit of a klutz. Actually, I’m a lot of a klutz. My leap, to use a term far grander than the motion deserved, carried me up a foot or so and partway out the window. Unfortunately, it carried me far enough out that I fell through the opening.

Some instinct made me spread my legs. I spread them wide enough to hook my feet around the corners of the window. That brought my fall to a jolting stop, but there was no way I could get back in. There was no way I wanted to drop to the ground, either.

Quite simply, I was stuck.

It was not a comfortable position. The blood was starting to rush to my head. My legs were beginning to get cramps, and my glasses had swung past my forehead. Several coins bounced off my ear as they slipped from my pocket. They struck with tiny clinks against the small stones in the flower bed below me. I thought about spending the next few months with both arms in plaster casts. It didn’t seem very promising.

“Hey, you in that much of a hurry for a movie?”

I looked down at the top of Splat’s head. Without my glasses in front of my eyes, everything was mostly a fuzzy blur, but I recognized his voice. This seemed to be my day for seeing heads from different angles. “I slipped,” I said.

“Need some help?”

“That would be nice. Do you think you could avoid mentioning my current predicament to my mom?” I knew that parents tended to worry about safety. If Mom saw me dangling like this, she’d probably have all the windows in the house sealed shut.

“No problem. I’ll be right up.”

I watched the top of his blurry head move toward the door. I knew he’d have no trouble. Mom would let him right in. She liked Splat. Just about everybody liked him. He was fun to have around. When he grows up, it wouldn’t surprise me if he became a senator or an actor or something like that.

There was a brief delay, during which I worked very hard on not slipping farther out the window. Finally, a pair of hands gripped my ankles.

“Hang on,” he said. “I’ve got you.”

Soon after that, I was back in my room. It felt good to be right-side up. I replaced the screen and flexed my leg muscles to get rid of the cramps.

“Care to explain?” Splat asked.

“Nope,” I said, shrugging.

“Come on, what were you doing?”

I walked over to the shelf that ran along the wall opposite my bed and took down one of my specimen jars—the one with the bees. “Have I shown you these? I just collected them last month. All the stingers are intact.” That was pretty mean of me. I knew Splat hated bugs, and I usually didn’t do this sort of thing, but I wasn’t sure what had happened and I didn’t want to talk about it.

“Well, let’s get going,” he said, backing away from me and the bees. “The movie starts in half an hour.”

“I can’t wait to see it,” I said, putting the jar back on the shelf.

As we headed toward town, I tried to understand what I’d done. I knew I’d sat down to start my homework. And I knew I’d ended up hanging out the window. It was the part in between that was unclear. I’d seen a squirrel. And I’d risen to get a better look at it. Then I’d gone to the window. Had I jumped at the squirrel? No, that’s not possible. I would never have attempted a stunt like that. I must have tripped or something.

By the time we reached the corner, I’d given up trying to figure out what had happened. As long as it didn’t happen again, it really didn’t matter. Right now, I had a date with some brain-sucking leech people.

On the way into town, we saw something else that got us talking. Stapled to a phone pole—stapled to many phone poles, we soon discovered—was a poster announcing the arrival of THE HULL BROTHERS’ CIRCUS: THREE RINGS OF THRILLS, CHILLS, AND YET EVEN MORE THRILLS.

“Sounds great,” Splat said, pausing in front of the pole. “I really like the circus.”

“I hope their performers are better than their posters.” I looked more closely at the advertisement. Actually, except for the rather weak headline, it wasn’t all that bad. There were colorful pictures of trapeze artists and high-wire walkers, along with an elephant, some horses, and lots of clowns. At the bottom of the poster, it said: SEE THE ELEPHANTS, SEE THE HORSES, SEE THE MONKEY BOY.

“Come on,” Splat said, “we’ll miss the beginning of the movie.” He jogged down the street.

I followed, dropping a bit behind. If I run too much, my glasses start slipping down my nose. I hate that. But I wasn’t sure whether Splat would wait for me at the ticket booth or go inside without me. If he went inside, I’d have a hard time finding him in the dark.

Sure enough, by the time I reached the ticket window, Splat was nowhere in sight. I bought my ticket and went in, hoping I could spot him before he sat down.

But it wasn’t as dark in the theater as usual. I found him right away—halfway down the theater on the left. The movie hadn’t begun yet, so I went to the snack counter and got some popcorn, a box of gummy eyes, and a root beer.

I reached my seat just as the film started. “Aren’t they going to shut off the lights?” I asked as I sat down.

Splat turned toward me, a puzzled expression on his face. “What do you mean?”

I rubbed my eyes. It was dark, I guess, but it didn’t seem as dark as normal. “Nothing,” I said. Then I dug into my snacks and settled down to watch the leech people suck the brains out of almost everyone in an unsuspecting town. All in all, it promised to be a satisfying afternoon. It would have been perfect if it hadn’t been for a little problem with the idiot behind me.

Five

HUSH

I hate it when people talk during a movie. It was just my luck that I had ended up one row in front of someone who must have been trying to become the King of the Movie Talkers. He jabbered and chattered and babbled without any sign of ever stopping. If a leech person appeared, he’d say, “Look, a leech person.” If someone was about to walk into a room where a leech person was hiding, he’d say, “Don’t go in, there’s a leech person.”

The talking by itself would have been enough to annoy me. What made it even worse was that the comments were so stupid, they were driving me out of my mind.

About halfway through the movie, I snap

ped. It wasn’t like me. Usually, I take whatever the world dumps on me in relative silence. I’ve had a lot of practice.

This time, I really lost it.

I turned around and shouted, “SHUT UP! JUST SHUT UP! PLEASE, PLEASE, PLEASE SHUT UP, YOU IDIOT!” My eyes scrunch up when I shout. If they’d been open, I would have been the one who’d kept his mouth shut. When I finally got a good look, I suddenly understood how a turkey feels on Thanksgiving morning. The kid sitting behind me was huge. He looked like a boulder with arms.

He didn’t say a word. For one long moment, he just stared at me with a confused frown. I could almost hear his brain clicking as the various facts of the situation forced their attention on him. As painful as thinking must have been for him, I could see from his face he had figured out a response to my shouts. He pulled his foot back, then shot it forward and kicked my seat.

I felt like a bowling pin. It’s amazing my bones didn’t go flying right out of my body. After the kick, he said, “I’m gonna get you.”

I looked over at Splat. “Maybe we should move,” I said.

“Good idea.”

We slipped from our seats. As I hurried away, I kept waiting for a huge hand to grab me by the shoulder and fling me through the air. Or maybe he would squeeze me like an accordion, playing music while he crushed various parts of my body.

But we made it out of the aisle and across the theater to the other side.

“That was not a healthy thing to do,” Splat whispered after we took our new seats.

“Who was that?” I didn’t recognize my new enemy.

“Got to be a Mellon,” Splat said.

“Yeah.” I nodded. The Mellons were born big. Lud and Bud Mellon went to our school. They had a lot of relatives. They used to be pretty mean, but had calmed down a bit recently.

“Speak of the devils,” Splat said, looking toward the entrance.

I watched as Lud and Bud came into the theater and walked up to the talker. “Sorry we’re late, Cousin Spud,” Lud said.

I turned to Splat and said, “Spud Mellon?”

“What?” Splat asked.

“They called him Cousin Spud.”

Behind us, someone said, “Hey, quit talking. We’re trying to watch a movie. What’s wrong with you? Ain’t you got no manners? Stupid kids…”

I slunk down in my seat and tried to enjoy the rest of the movie. I hoped that Cousin Spud would forget about me—a likely action for a Mellon—or not recognize me the next time we met. If it was dark, I’d have a chance, but the theater was so much lighter than usual that I had little hope of being saved by the dimness of the room. I’d just have to depend instead on the dimness of the Mellons.

Still, I had yelled at someone much bigger and survived. That should have made me feel wonderful, given how few victories I’ve experienced in the physical world. But all I could think about was what would happen if he decided to carry out his threat. On top of that, my neck started itching. I scratched, enjoying how fabulous my nails felt against my skin. They seemed longer and sharper than usual. I guess I’d neglected to cut them recently. That was odd. I usually paid great attention to personal grooming.

My back itched, too.

Six

HERE’S LOOKING AT YOU

“Well, I think I’ll go home and tell Rory about the movie,” Splat said as the film ended. “Want to come?”

I knew he liked to share the stories with his little brother. Rory wasn’t allowed to see horror movies, but Splat always gave him a mild version of the story so the kid would feel he’d been there with us. I liked Rory—he was a lot of fun for a miniature person—but I felt a need to be by myself. “I think I’ll head home,” I said.

“Okay, see you tomorrow.” Splat dashed down the aisle toward the back exit.

I looked around. The Mellon brothers and Cousin Spud were heading out the same way. Apparently, at least for the present, I’d been forgotten. It’s one of my special talents. I have a magic ability to slip from people’s minds. Right now, at least, I was glad to have such a skill.

I went out a side exit that led to an alley. There wasn’t much of a crowd, and I found myself alone. As I started to walk toward the street, my back suddenly felt funny. It was as if I knew there was someone behind me. I spun around and looked. There was nobody there.

Then I looked lower.

I saw a man sitting in the alley, scrunched against a wall, one leg stretched out, the other folded at the knee. He was wearing faded and torn clothing. I’d walked right past him without noticing. For an instant, I tensed. Then I relaxed. I recognized him. His name was Lew. He was always hanging around town, but he never bothered anybody. Kids sometimes joked that he owned the town, since it’s called Lewington.

He was looking down at the ground, or at nothing. But after I turned toward him, he raised his head. For a second, he glanced my way, his eyes seeming totally without interest. Then something odd happened. As his head started to drop down, it snapped up again, and he stared at me. It was as if he suddenly realized that he’d seen something different from what he expected.

I backed up a step. “What are you looking at?” I asked.

He didn’t answer. He just kept staring.

I stared back, briefly. Then I spun away and raced out of the alley. For some reason, I felt I had to flee from him. This was his alley. I didn’t belong there.

I was running.

That was not something I did very often. It was certainly not something I enjoyed.

Until now.

I was running, and it felt … good. I reached the edge of the alley and turned onto the sidewalk. I kept running, breathing deeply. Did I need to pant? I realized I was breathing that way out of habit. Before, whenever I’d run, I had to gasp for breath. But this time, my lungs didn’t ache. I slowed my breathing down.

I ran. The air rushed past me as I cruised over the sidewalk and moved through town, each foot barely touching the ground. My stride was so smooth, my glasses hardly bounced.

So this was what it felt like.

I thought I could run forever.

But halfway home, I began to breathe heavily. Another block, and I began to pant. I slowed down. Then I had to stop. For several minutes, I stood, unable to move. I bent over and rested my hands on my legs. After a while, I could breathe again. I walked slowly toward my house.

I wiped my forehead, then looked at my right hand. There was no sweat. That was odd—I felt hot and was still panting a bit. The cool air felt wonderful as I drew it over my tongue. Something else was wrong. It took a moment for me to notice, but once I saw it, the strangeness leaped out at me. My third finger was the same length as my middle finger. I stared at my hand, then looked at the left one. It was the same way.

I was almost positive they hadn’t been this way before, but the evidence was right in front of my eyes. Maybe I was having a growth spurt.

Walking down the street, holding my hands in front of me, I realized I must have looked like someone carrying an invisible tray, or like a movie monster carrying the woman who had just fainted at the sight of him. I let my hands drop and walked the rest of the way home.

“How was the movie?” Mom asked when I came in.

“Great. Best brain-sucking leech movie ever. Brains were flowing like water. It was terrifically gross,” I said. “What’s for dinner?”

She sort of grinned and pointed over her shoulder with her thumb, directing my attention to the counter. There, stacked four high and six across, were aluminum food containers—the kind she used when she was catering. “You know that lamb curry you liked so much?” she asked.

“Someone cancel out on you?”

“Yup. The McKlosky wedding just turned into the McKlosky War. It seems the bride and groom discovered that they really don’t want to spend the rest of their lives together. At least they figured it out before they went through with it. But the wedding is off, and I’m stuck with many gallons of lamb.”

It was a good thing I

liked the curry. Once, Mom had gotten stuck with five pounds of chopped liver. There were a lot of happy dogs in the neighborhood that week.

I helped Mom take most of the containers down to the freezer. The smell was wonderful, and I was almost drooling with hunger by the time we were finished.

By then, my dad had come home from the college. He teaches chemistry there, but he’s interested in everything. I guess I’m a lot like him, though he really gets lost in his thoughts pretty often, and has a hard time noticing the world.

We dined on the curry. The chunks of meat seemed especially tasty. I really wolfed my meal down. At one point, Mom even gave me a look and said, “Slow down, it’s not going anywhere.”

After dinner, as Dad and I were cleaning up, the doorbell rang. Mom answered it, then returned to the kitchen. “Norman,” she said, seeming slightly puzzled, “there’s a man to see you.”

I put the dish towel back on the hook and went down the hall. There, standing at the open door, was a man dressed in safari clothes. Something about him looked familiar.

His face—that was it. He had the same face as Husker Teridakian, the bumbling vampire hunter who had gone after Splat. But beyond the face, there was no resemblance. Where Husker had been a small man, this person at my door was at least six feet tall and built like a football player.

“Norman Weed?” the man asked, extending a hand. His voice was deep and full of confidence. This was not a man who worried about the small things in life.

I nodded and watched as my own hand vanished within his grip. I sensed that he could crush my fingers to mush if he wanted to.

“Teridakian,” he said. “Zoltan Teridakian. My brother spoke to me of you. I am a hunter, also. But of another sort. I believe you can help me.”

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo

Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus

Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus Emperor of the Universe

Emperor of the Universe Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool

Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets

Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy

Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy Numbed!

Numbed! Punished!

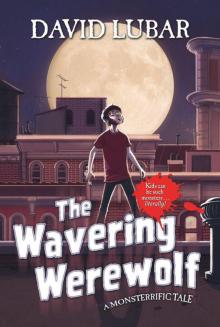

Punished! The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales)

The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales) Dog Days

Dog Days Sophomores and Other Oxymorons

Sophomores and Other Oxymorons The Psychozone

The Psychozone My Rotten Life

My Rotten Life Invasion of the Road Weenies

Invasion of the Road Weenies In the Land of the Lawn Weenies

In the Land of the Lawn Weenies Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies

Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies Ghost Attack

Ghost Attack Check Out the Library Weenies

Check Out the Library Weenies Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book)

Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book) Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories

Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories Hyde and Shriek

Hyde and Shriek The Wavering Werewolf

The Wavering Werewolf Dead Guy Spy

Dead Guy Spy Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies

Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies The Big Stink

The Big Stink The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies

The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies Character, Driven

Character, Driven The Bully Bug

The Bully Bug Beware the Ninja Weenies

Beware the Ninja Weenies Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge

Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge The Unwilling Witch

The Unwilling Witch Goop Soup

Goop Soup Lay-ups and Long Shots

Lay-ups and Long Shots The Gloomy Ghost

The Gloomy Ghost Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie

Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories

Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories Attack of the Vampire Weenies

Attack of the Vampire Weenies Enter the Zombie

Enter the Zombie The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale

The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale The Curse of the Campfire Weenies

The Curse of the Campfire Weenies The Vanishing Vampire

The Vanishing Vampire