- Home

- David Lubar

In the Land of the Lawn Weenies Page 6

In the Land of the Lawn Weenies Read online

Page 6

“I don’t know,” Stu said.

“How about the dump?” I suggested.

Stu’s face creased with a frown. “But there might be …” He stopped, and the frown faded. Then he smiled. “Sure,” he said. “Let’s go.”

YOUR WORST NIGHT MARE

It’s over. The nightmare is over. Just in time. I couldn’t run much farther. I could hardly breathe. Larry looked even worse. But we didn’t have to run. I’d saved us. My idea worked. I could stand here now and catch my breath and wonder how things had gotten so quickly out of hand.

I probably shouldn’t have been hanging out with Larry in the first place. He can be a really big jerk. But I’m not too good at making friends, so I didn’t have a lot of choices. I usually ended up spending my free time with Larry. Mostly, I didn’t get involved when he was being a jerk. I didn’t try to stop him, but I didn’t take part.

But the Clayton kid blamed both of us. It was all Larry’s doing. That didn’t matter. We both got blamed.

I don’t know where Larry got the phrase—probably from some movie. That’s how it started with the Clayton kid. What was his name? Ricky. That was it—Ricky Clayton. He’s this real quiet kid who doesn’t ever bother anyone or do anything much at all. Even so, there’s something spooky about him.

But mostly I guess he was in the wrong place at the wrong time. He was walking down the street toward Larry when Larry was in that mean mood of his.

“Hey, what are you looking at?” Larry said as the kid got close to him.

“Nothing,” the kid mumbled. I guess he didn’t realize what a dangerous answer that was.

“Nothing? You calling me nothing?” That’s when Larry grabbed the kid by the shirt. Larry really liked to do that. He’d grab a handful of cloth and buttons, right below the neck, and then twist his fist. I think he’d gotten that from a movie, too.

“Come on, leave me alone.” The kid squirmed a bit but didn’t try to break loose.

“You know what I am?” Larry asked him. I could tell he was getting ready to use the phrase.

The kid shook his head.

“You know what I am?” Larry yelled, putting his face right up close so his nose was almost in the kid’s eye.

“No …”

“I’m your worst nightmare.” Larry gave the kid a push.

The kid stumbled backward and fell down hard on his butt. I expected him to start crying, or to turn and run. He wasn’t very big. Larry would never do something like that to anyone who had a chance of fighting back. But the kid didn’t cry or run. Instead he stared at Larry and said, “You don’t know anything about nightmares.”

I guess that took Larry by surprise. He didn’t say a word. Then the kid spoke again. “But you will. Real soon.” He stood up slowly, his eyes still locked on us. “Your worst nightmare is coming. It’s on its way.”

“You’re crazy,” Larry said. He shook his head. “Let’s get out of here. This kid has lost his mind.”

I didn’t need much convincing. The Clayton kid was far too strange. We walked away. Behind us, I heard the kid say, “For both of you.”

As we went down Lincoln Street, the breeze picked up. The air filled with whirling maple seeds that had been blown down from three trees that grew in the yard of a house near the corner.

Whenever I saw Larry rough up someone, I found myself acting extra friendly afterward, sort of wanting to make sure he still liked me. Maybe that’s why I started to tell him my deep secret. “Hey, you ever pretend that those seeds are—”

“What was that?” Larry said, pointing in front of us.

I didn’t see anything. “Where?”

He shook his head. “Nothing. Let’s go this way.” He turned down Spring Street.

“Sure.” I followed and thought about spilling my secret. But Larry had other things to talk about.

“Did you see that kid’s face when I pushed him?” he asked, grinning. He opened his eyes wide, imitating the kid, then snorted in amusement.

“Yeah, he really looked surprised,” I said.

“Bam, right down on his butt,” Larry said. “That’ll teach him to show me some respect.”

“You got that right,” I said.

We’d gone less than a block when Larry stopped again. This time he just stood there and pointed.

This time, I saw it.

He must have been close to seven feet tall. He might have been alive once. Imagine a man made inside out. Give him claws. Give him fangs and an attitude. Now imagine something twice as awful. That’s what stood in front of us. If he caught up with us, I think we’d get torn to pieces quicker than you could let out a scream. From the muscles that rippled on the outside of his arms, I know he could pull us apart as easily as a couple of wet napkins.

Larry turned and ran down Spring, crossing Lincoln. I stuck right with him.

“What was that?” I managed to ask as we ran.

“My nightmare,” Larry told me. “My worst nightmare.”

“Oh man. You dream that kind of stuff?” Before Larry could answer, we had to stop. The monster from his nightmare was in front of us, at the corner of Spring and Hickory.

This time, he was closer.

Just like in a nightmare.

We cut down Spring Street. “Let’s go to one of the houses,” I said. “Let’s get inside.”

“No. I do that sometimes in the nightmare. Then I’m trapped.”

“Do you ever get away?” I asked.

Larry shook his head. “He always catches me.”

We ran. He chased us, but he always ended up ahead of us. “We’re dead,” Larry gasped. He was panting so hard he was spraying spit with each breath. “That kid. He did this.”

I thought about the kid. As we’d left, he’d said, “For both of you.” For Larry for what he’d done, and for me for standing there and letting it happen. The very thought of my worst nightmare coming to life made my guts churn. But maybe two bad things could cancel each other out.

“This way,” I said, heading back toward Lincoln.

Larry followed. He was starting to moan softly each time he breathed. I think he was running out of strength. “Sometimes, I find a gun,” Larry said, gasping between sentences. “I shoot it, but it keeps coming.”

“This time is different,” I said.

We made it to Lincoln. We had to keep changing direction on the way. But we made it. I stopped before we reached the maple trees. “We can rest here,” I told Larry. “We’re safe.”

“What … ?” That was all Larry could get out.

“That’s my worst nightmare,” I said, looking at the trees.

“Huh?” Then Larry pointed toward the corner. “Got to run.” His nightmare stood ahead of us, at the other side of the maples.

“No. Let him come.”

I waited. I think Larry still wanted to run, but he couldn’t find the strength. I watched the seeds whirling down, imagining what would happen if they suddenly became as sharp as razors.

A stray seed whirled at me, caught by a gust of wind. The seed glanced off my forehead. I could feel something warm and wet running down my face. Blood. In front of us, Larry’s nightmare slowly lurched forward. But it was almost over. Larry’s worst nightmare was about to walk right through my own worst nightmare.

“We’re okay,” I said.

“You’re bleeding.”

I shook my head. “Doesn’t matter.” I held my breath for a moment as Larry’s nightmare tried to pass through the cloud of swirling seeds. It was like watching tomatoes in a blender. I had to turn away. I looked at Larry’s face. He was staring straight ahead, watching his nightmare get shredded.

“My nightmare …” He still hadn’t caught his breath.

“It’s okay,” I said. “It’s over.”

“My nightmare,” he said again. He kept staring. I didn’t know how he could stand to look at that mess. “Sometimes, I find an ax.” He took a small step backward.

“It’s over,” I said.

I risked a peek beneath the maples. Larry’s nightmare was now thousands of scattered shreds.

“I use the ax. I chop my nightmare to pieces.” He took another step back. Then he grabbed my shirt and twisted it and put his face an inch from mine. “It doesn’t matter. The pieces just keep coming.”

I looked past Larry to the spot where his nightmare should have ended.

“No,” I gasped as my blood froze in my veins and my muscles fell slack from fear. “No …”

Larry was right. The pieces were coming. They were small. But they were fast. Suddenly, the maple seeds didn’t seem all that awful. Suddenly, I had a new worst nightmare. I tried to run, but the pieces were everywhere.

PHONE AHEAD

Normally, Joe wouldn’t pick through garbage, but he’d glimpsed the edge of a shiny plastic case in the trash basket on the corner of Watson Street. Electronics, he thought as he leaned over and reached inside. Oh yes. Whatever it was, it certainly wasn’t trash. Who would throw out a cellular phone? Joe wondered as he pulled the object from its nest of crumpled papers and crushed cans.

“Probably doesn’t work,” he said to himself as he flicked the on/off switch and held the phone to his ear. That’s when he got his first surprise of the day. He heard someone talking. Joe listened for a moment, then said, “Hello? Hey, I found this phone. Can you hear me?”

But the voice on the other end didn’t respond to him. The man was speaking to someone else. “I just saw it on the news,” the man said.

“Lucky everybody got out,” a woman said. “Can you imagine what would have happened if there were lots of people in the bus station when the fire started? That would have been terrible.”

The bus station ? Joe thought. He hadn’t heard anything about a fire, and he hadn’t heard any sirens. But if the man just saw it on the news, it might still be happening. Joe had to go see. He switched off the phone and slipped it in his pocket. Then he jogged to the bus terminal.

“They must be crazy,” he said when he reached the station. There was no sign of a fire. Joe looked at the clock on the bank across the street. It was seventy-four degrees. It was ten in the morning. He went home and put the phone in his desk drawer.

That evening, Joe was walking through the living room as his parents watched the news. “A fire broke out at the bus station around five this evening,” the announcer reported.

Joe couldn’t believe it. He listened to the rest of the story, trying to compare the details to what he had heard on the phone.

“No one was hurt, but the station was badly damaged. We’ll have more information on the eleven o’clock report.”

A shiver ran down Joe’s back, then twisted through his stomach. He rushed to his room and grabbed the phone. He switched it on, but all he got was dead silence.

He tried the phone again an hour later. The line was still dead. But on the next try, right before he went to bed, Joe heard the two people talking again.

“I just hate this weather,” the man said.

Joe looked out the window. Stars twinkled in a cloudless sky.

“I don’t mind the rain,” the woman said, “but ever since I was a kid I hated thunder.”

Joe could hear a crackle over the line like there was lightning in the air. Definitely crazy, he thought as he turned off the phone and went to sleep.

Six hours later, clouds filled the night sky. A heavy rain fell. The first thunderclap woke Joe. Lightning danced across the clouds in jagged flashes. Maybe they aren’t crazy, Joe thought as he watched the storm.

Joe started checking the phone as often as he could. Whatever the man and woman talked about—the weather, the news, the latest episode of their favorite television show—happened just as they said. But each event took less time to come true than the last. The future Joe overheard in the phone kept getting closer to the present. But none of it was worth anything to him.

The next day, Joe finally heard something exciting.

“Imagine that,” the man said. “All those bags of money lying there—right on Adams Street, just past the corner at Main.”

“Can you believe it was there for over an hour before the police found it?” the woman asked. “The robbers must have dropped the loot when they were getting away. Good thing Adams isn’t a busy street. It’s still pretty amazing nobody picked up the money.”

Joe switched off the phone. This was better than knowing the weather or the news. This was information he could use. Main and Adams streets were less than half a mile away. Joe started running. He reached Main and headed toward Adams. As he turned the corner, he saw bulging canvas bags scattered across one side of the street.

Joe ran down the block, his eyes fixed on the sacks. A police car came speeding past. It slid to a stop right next to the money. Two officers jumped out, grabbed the sacks, and tossed them into the trunk.

“Stupid phone,” Joe said as he watched the patrol car drive away. He was so frustrated he almost threw it in the garbage. What good was knowing the future, he asked himself, if he couldn’t get there in time?

Joe started walking home, holding the phone in his hand. He kept wondering what the man and woman were discussing right now. Probably chatting about the weather, he thought. Or something stupid, like a new movie. But maybe it was something really important …

Joe felt like he was holding onto the last piece of popcorn from a box. He couldn’t leave it untasted. He had to try again. As he started across Bridge Street, he switched on the phone. Tell me something I can use, he thought. That’s all I want. Tell me something important. Just one small thing.

He held the phone to his ear. They were talking. Joe relaxed. Hearing the voices was like running into old friends.

“Poor kid,” the woman was saying.

There was a sadness in the woman’s tone that caused Joe to stop walking and listen carefully.

“Yeah, I saw it on the news. It’s a shame he died.”

Joe shook his head. “Who cares,” he muttered. This didn’t sound like anything useful or important. But he kept the phone to his ear. He couldn’t help himself.

“He was just standing there,” the man said, “right in the middle of Bridge Street, by the place where the road curves. Imagine that. I wonder what was on his mind? They say he didn’t even see the truck.”

Truck? Joe thought as he heard the blare of a horn and the shriek of large tires skidding around the curve behind him. What truck?

“Cool,” Lisa said as she looked down into the garbage can next to a lamppost on Bridge Street. She reached inside, wondering why someone would throw away a cellular phone. “Probably doesn’t even work,” she said. She switched it on and held it to her ear. She smiled as she heard voices. This, she thought, could be very interesting.

SAND SHARKS

Kelly had the sand castle almost perfect when Michael ran across the beach, screaming like a wild man. He smashed right through her marvelous castle, blowing it into fine fragments of sand that fell in a shower around her.

“Michael!”

“Sorry,” he said, barely glancing over his shoulder. “Didn’t see it.”

“Yes you did. You ruined it on purpose.”

Michael turned toward Kelly and shook his head. “Didn’t,” he said in a calm voice.

“Did!” Kelly shouted.

“Kids,” Dad said, looking up from his magazine. “Stop fighting. This is supposed to be a vacation. Kelly, you’re old enough to know how to behave. You should set an example for Michael.”

“But Michael ruined my castle,” Kelly said. “And he did it on purpose. Just like he ruins everything.”

Mom glanced up from her book. “I’m sure it was an accident. There’s no need for all this shouting.” She shifted her eyes back to her reading before Kelly could answer.

Kelly looked at Michael. Michael looked back, grinning. Then, as if to make sure she knew it was no accident at all, he stuck out his tongue.

Kelly grabbed a fistful of sand, squeezing it so hard she

could almost imagine it forming into a hunk of rock. It would feel wonderful to hurl it at Michael. That would knock a little manners into him. Her arm tensed.

“Listen, kids,” Dad said, “your mom and I want to go back to the hotel and pick up some lunch for everyone. Can we trust the two of you to stay here alone?”

“Sure,” Michael said. “No problem.”

Kelly let the sand trickle from her fingers. Alone out here? The place was so bare and empty. They were the only people on the beach, and there weren’t a whole lot of people on the island. A dozen frightening thoughts flashed through Kelly’s mind.

“Well, Kell?” her Dad asked.

“Better take her with you,” Michael said. “She’s scared.”

“Am not,” Kelly said. She looked at her dad. “Sure, we’ll be fine.” The words fell from her mouth like specks of foam at the edge of a wave. In an instant, they were lost on the beach.

“Stay out of the water,” Mom said. “We’ll hurry back.”

Kelly watched her parents walk up the beach to the road and wedge themselves into the small rental car. In a moment, the car was puttering along the narrow pathway. In another moment, it was out of sight.

Michael headed right for the ocean.

“Hey,” Kelly said, “they told us not to.”

“They aren’t here, are they?” Michael walked deeper, kicking up water with each step.

Kelly glared at him. I hope you drown, she thought. Instantly, she felt awful for making such a terrible wish.

Michael screamed.

Kelly’s heart slammed against her chest. Her brother slashed his arms down, striking at something in the water. He screamed again. Then he lurched and disappeared beneath the water.

“Michael!” Kelly ran to the edge of the ocean. She searched for any sign of her brother. She rushed into the water, unsure of what to do. “Mom! Dad! Come back! Help!” Kelly yelled toward the road. It was useless. They were gone. She ran farther out. The surf lapped at her knees. “Michael, where are you?” she called, desperately scanning the ocean.

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo

Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus

Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus Emperor of the Universe

Emperor of the Universe Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool

Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets

Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy

Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy Numbed!

Numbed! Punished!

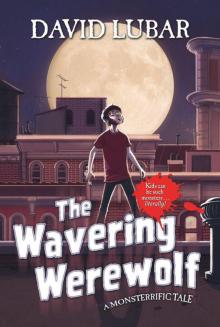

Punished! The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales)

The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales) Dog Days

Dog Days Sophomores and Other Oxymorons

Sophomores and Other Oxymorons The Psychozone

The Psychozone My Rotten Life

My Rotten Life Invasion of the Road Weenies

Invasion of the Road Weenies In the Land of the Lawn Weenies

In the Land of the Lawn Weenies Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies

Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies Ghost Attack

Ghost Attack Check Out the Library Weenies

Check Out the Library Weenies Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book)

Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book) Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories

Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories Hyde and Shriek

Hyde and Shriek The Wavering Werewolf

The Wavering Werewolf Dead Guy Spy

Dead Guy Spy Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies

Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies The Big Stink

The Big Stink The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies

The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies Character, Driven

Character, Driven The Bully Bug

The Bully Bug Beware the Ninja Weenies

Beware the Ninja Weenies Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge

Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge The Unwilling Witch

The Unwilling Witch Goop Soup

Goop Soup Lay-ups and Long Shots

Lay-ups and Long Shots The Gloomy Ghost

The Gloomy Ghost Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie

Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories

Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories Attack of the Vampire Weenies

Attack of the Vampire Weenies Enter the Zombie

Enter the Zombie The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale

The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale The Curse of the Campfire Weenies

The Curse of the Campfire Weenies The Vanishing Vampire

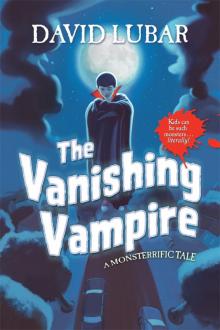

The Vanishing Vampire