- Home

- David Lubar

Beware the Ninja Weenies Page 7

Beware the Ninja Weenies Read online

Page 7

Mandy crawled through the softness of the wall.

It was brighter on the other side. She was in a large field of grass. Ahead, she saw all sorts of objects scattered across the ground.

My things!

She spotted her skates right away. One was up on all four wheels; the other lay on its side, as if the journey had exhausted it. Nearby, she saw her pen.

She strolled among the lost treasures—things she knew were missing and things she didn’t even realize she’d lost. The farther she walked, the older the things became. At the far end of the field, where it met a stream, she found things she didn’t even remember owning. There were baby toys, clothes, a board book with teeth marks on the cover, and a small teddy bear.

Mandy looked ahead, and then back the way she’d come. The land seemed to stretch forever in all directions.

“Everything in here is lost,” she whispered. “Everything…”

She looked for a path back to her house. There was nothing to see but open land.

Elsewhere, in the world she’d left, there would soon be a poster asking if anyone had seen Mandy. LOST GIRL the message at the top would read. PLEASE CALL IF YOU SEE HER.

Nobody ever saw her. Nobody ever called.

CATFISHING IN AMERICA

Every summer, I visited my cousin Vince in Alabama. I loved it. All we did was swim, fish, and go rafting. The river was Vince’s playground all year round.

Vince and his folks lived right near the water. We’d taken their rowboat out to a small island that morning, and had been fishing for sunnies all day.

There are bass and some perch in the river, too. Bass are exciting to catch, but sunnies are fun because they’ll bite at anything. I’ve even caught them on a bare hook once or twice. They go especially crazy over red worms—the skinny little ones, not the fat night crawlers—and we’d dug a ton of those in Vince’s backyard, right next to his mom’s vegetable garden.

As the sun started to touch the horizon, Vince reeled in his line and got up from the rock he’d been sitting on.

“Where you going?” I asked. I checked the bucket next to me. I still had tons of bait wriggling in the dirt, and there’d be plenty of light for at least another half hour.

“It’s getting dark,” he said. “We need to go back.”

“Why?” I was having a great time.

“Catfish will come out soon,” Vince said.

I couldn’t help laughing. “Catfish? What are they going to do—jump out of the water and bite us?”

“Maybe,” Vince said.

His voice was so flat, and his face so serious, that I felt a strange tug in my gut. I’d caught enough catfish to know you had to be careful handling them. They had these whiskers—called barbels—that could punch a hole into your hand. It stung real bad. They had spikes in their fins, too. And they had teeth that looked kind of like fangs. But none of that had anything to do with sunset, and none of it should have scared my cousin. “What’s going on?” I asked.

“The catfish around the island—they’re different. Everyone who lives here knows it, even if nobody talks about it. Come on. Let’s go. We can come back tomorrow.”

“No way.” I slid off the fallen oak I’d been sitting on and walked over to Vince. “That’s silly. Fish are fish. Whatever you heard—it’s nothing more than some sort of story people tell to scare kids, like the bogeyman and all that nonsense.”

“You’re just a city boy. You don’t understand this stuff.”

“And you’re just a hick,” I said.

Vince gave me a push. “Them’s fighting words.”

I could have gotten angry, but I’d been pushed a lot harder. I go to a pretty tough school in the city, and I’d been in my share of fights. So I wasn’t feeling the need to push back or to prove anything. I was more interested in seeing if I could get Vince angry.

“Thems?” I said, mocking his accent. “Where’d you learn English? A haystack? Where’d you learn biology, for that matter? I’d call it ichthyology, but that’s one of those big city words you wouldn’t understand. I can’t believe you’re scared of some stupid catfish.”

Vince glared at me. He was so angry, I could see his body quiver. Maybe I’d pushed him too far. I thought about what I’d just said and realized it had been way too mean. I guess it wouldn’t hurt to apologize.

As I was trying to figure out the best way to tell him I was sorry, he crossed his arms and said, “All right, then, city boy. Let’s stay.”

He looked like someone who’d just volunteered to take part in a firing squad—and not on the shooting end.

“Nah, let’s go,” I said. “I’m tired of fishing.” I thought back to other summers. I couldn’t remember ever fishing in the river after dark. Or swimming. Vince had always found something else for us to do before the sun had fully set.

He walked over to the rowboat where we’d beached it on the bank, and gave it a push with his foot.

“Hey! Are you crazy?” I watched as it got caught by the current and swept away.

“I guess we’re staying,” Vince said.

I pointed downriver, where the boat had almost moved out of sight. “You lost the boat!”

Vince shook his head. “Nope. She’ll wash up at the bend in the shallows just before where Nashamuk Creek feeds in. The boat’s not lost. But we’re stuck here until someone comes looking for us, city boy.”

I watched the boat sweep around a bend. “When will that be?”

“My folks are out at the square dance,” Vince said.

Before I could make a comment, he pointed a finger at me. “One joke, just one little joke about square dancing, and you’ll be drifting in that current, too.”

I held up my hands. “Hey, I’m not saying a word.”

I picked up my rod and reached for a worm. I figured I might as well get back to fishing.

“Let’s build a fire first,” Vince said.

“Why?” I glanced toward the horizon, where a three-quarter moon was rising in the cloudless sky. “There’s plenty of light.”

Vince muttered something that didn’t sound very polite and stepped into the small cluster of trees behind us. He came back five minutes later with an armful of deadwood, which he tossed to the ground with a bit more force than was necessary. “Got any matches?” he asked as he patted his pockets.

“Nope. Why would I carry matches?”

“It’s always smart to carry matches,” he said. “Just in case you need to make a campfire.”

“I’ll try to remember that the next time some idiot strands me on an island.”

The sun was gone now, though the sky was still more blue than black. A dark shadow moved near the edge of the water. I stepped toward it, but Vince grabbed my shoulder. “Stay back.”

I pulled away from his grip and walked over to the bank.

“Whoa—it’s a catfish.”

That’s what it was. A small one, compared to the river giants—maybe a foot long. I bent down to take a closer look.

The dark gray catfish, which was just below the surface, lifted its head out of the water, opened its mouth, and hissed at me. Yeah—it hissed. As I leaped back, I caught sight of fangs in its mouth. Four fangs—two on top and two on the bottom. They were a lot longer than any fish teeth I’d ever been this close to before.

“Did you see that?” I shouted.

“I tried to warn you,” Vince said.

I could feel my heart thumping in my chest. I took a breath and told myself there was nothing to worry about. “It’s just a fish.”

“There’ll be more,” Vince said. “And they’ll be bigger. The small ones aren’t smart enough to wait until the light is totally gone. But all of them, big or small, like to hunt for warm blood.”

I looked at the river, where dark shapes gathered beneath the surface. “We have to build that fire,” I said.

Vince shrugged. “I wish we could.”

A couple more catfish had moved up to the shore. Then one or two wriggled ont

o the bank. More fish followed them.

I checked behind me. The wooded area wasn’t big—maybe twenty or thirty feet across. Past that was the other bank of the island. I walked along the shore, keeping away from the catfish. I went all the way around the island. Even though I was moving slowly, watching my step for rocks and tree roots in the moonlight, it didn’t take more than five or ten minutes.

“They’re coming out all around us,” I said. I grabbed one of the sticks from Vince’s pile. “Maybe we can beat them off.”

I walked toward the closest fish and took a swing. The fish snapped at the stick, biting off the end.

“This is crazy!” I shouted. “Vampire fish? No. I’m not going to accept that. And I’m sure not going to let anything suck out all my blood on a stupid island in the middle of a stupid river.”

Vampire fish.

My mind churned with ideas, trying to think of a way out. We could swim for the bank, but if the river was filled with those fish, we were just handing ourselves to them.

“Okay,” I said, talking as much to myself as to Vince. “How do you kill vampires?”

“Wooden stake,” Vince said. He tapped the fishing knife on his belt, then pointed to the piece of wood I’d dropped. “I could whittle a point on it.”

“We’ll need a whole lot more than one stake,” I said. Dozens of the catfish had moved onto the shore and were wriggling toward us. I figured they’d reach us in another minute or two. “We could climb a tree,” I said. “And stay there until sunrise.”

Vince sighed. “I think they can climb, too. I found a dead squirrel in a tree by the river last year. It had been sucked dry.”

I almost gave up. But I thought about all those vampire movies where the vampire sizzles and crackles in the light of the sun. The real sun was hours away. But these weren’t real vampires. They were fish vampires. So maybe I could hurt them, or hold them off, with a different sun.

I grabbed my rod, baited the hook with a red worm, and cast over the catfish into the current.

Two seconds later, I felt a tap on my line. A small tap. Perfect.

Don’t mess up.

This was something I’d done a thousand times before, without thinking. Now it was hard not thinking what would happen if I failed. I tried not to let my mind get in the way of my reflexes. Luckily, I managed to time things just right.

I set the hook and reeled in the line, giving it a yank as the fish reached the bank. It flew over the catfish and landed in my waiting hand.

I held it up high and hoped I was right.

The moonlight glinted off the sunfish. The scales sparked like dazzling gems. The catfish hissed and gasped. They wriggled away, turning back toward the water. A couple of the smaller ones rolled on their sides, thrashed like they’d been stabbed, and burst into flames.

Vince took a branch over to a burning catfish and held it against the body until the stick caught fire. He used that to get the rest of the woodpile blazing.

I held up the sunnie until I was sure all the catfish had fled. Then I unhooked the fish and put it gently back in the water. I figured I owed it a safe return.

Once I was sure the banks were clear, I joined Vince at the fire.

“Pretty smart for a city boy,” he said.

“Dang…” That was about as much as I could say at the moment.

“Careful,” he said. “You’re starting to sound like a country boy.”

“There are worse things.” I said.

Across the river, I heard the sound of a motorboat. His folks were coming for us. We’d made it.

POSER

I’d spent the morning walking around town, trying to find a summer job. No luck. Maybe I should have started looking before school ended, or during the first month of summer vacation, but I sort of put it off. Now, partway through July, it looked like all the jobs for kids had been snatched up.

I was heading home when I saw the poster. The ad was hand-printed in colored pencil on a sheet of paper that looked like it was torn from a drawing pad.

ARTIST’S MODEL NEEDED. MALE. AGE 10 TO 12. GOOD PAY IF YOU CAN STAND STILL.

There was an address at the bottom. I was pretty sure it was just a block or two away.

I realized there was a chance this could be some sort of trick. There were lots of creepy people out there. They were always warning us about that in school, and showing us safety videos with smiling people in vans who were pretending to look for lost puppies. But I wasn’t going to walk into some place without making sure I was safe. I was too smart for that. I got my phone and called my friend Tyler.

“What’s up?” he asked.

“I’m checking out this job. It’s probably okay, but I don’t want to take any chances. I’ll keep my phone on. If you hear me yell or anything, hang up on me and call 911. Okay?”

“Sure. I’ve got you covered.”

I told him the address. I really didn’t think there was any sort of danger—not when the ad was posted right out there on the street, where anyone could see it—but it’s always a good idea to be careful.

The place was right where I thought it would be. The guy who answered the door looked like he was around thirty years old. He had a small paintbrush in his hand, and paint smears on the old denim shirt he was wearing. The odor of turpentine and bacon drifted out through the doorway. I guess he lived there. Past him, in a room down the hallway, I could see all sorts of artist’s stuff, like an easel and a bunch of canvases.

“What do you want?” he asked.

“The job for an artist’s model. That was your ad, right?”

“Oh, yeah.” He stepped back and stared at me for a moment, tilting his head different ways. “You’ve got the perfect look. Can you stand still for an hour at a time?”

“Can I wear my earphones?” I asked.

“Sure. As long as you don’t bounce around.” He started to walk down the hallway, then spun back and said, “Well, don’t just stand there.”

I followed him in, and he put me right to work. Though it felt weird to call it work, since all I had to do was stand there with my arms raised and my fists clenched like I was banging on a wall. While he was setting up his supplies, I pulled out my phone and told Tyler everything was okay.

“So I don’t get to call 911?” he asked.

“Sorry. No.”

He sighed. “Maybe next time.”

The artist had finished setting out his stuff, so I put my phone away. He told me his name was Caspar. No first or last name. Just Caspar.

Whatever.

He had a large sketch pad on an easel in front of him, and a piece of charcoal in his hand. “This is just a study. The real piece will come later. But it’s a great commission. The most important work I’ve ever been asked to do.”

He got quiet for a minute or two as he sketched. But then he started talking again. “The piece will be called Child of the New Decade Raging Against the Past.”

“Child?” I asked, trying not to move as I spoke. This reminded me of being at the dentist.

“Don’t take it personally. It’s just a label. The important thing is for you to look angry.” He sketched some more, stepped back, stared at the pad, stepped forward, tore the page off, and let it drift to the floor. Then he started a new sketch.

And that was my workday. It was hard keeping my fists clenched for so long, but he gave me a break once in a while so I could put my arms down. He paid me in cash when we were finished.

“Is that it?” I asked.

“No. Far from it. We’ve just begun. There’s too much at stake here to leap straight into the final stage. Every step requires thought. Tomorrow, I’ll get out the paints.”

That was fine with me. I was happy to know I had more money coming. My muscles were stiff from all that posing, but it wasn’t any worse than some of the stuff they made us do in gym class. And I never got paid for push-ups.

During the next two days, Caspar painted a large canvas on his easel. He kept asking me

to lean forward more. I tried, but it was hard keeping my balance.

The day after that, when I showed up at the studio, there was a glass box in the spot where I usually posed.

Caspar swung out one side of it, like a door. “Step in,” he said.

“Why?

“The final piece involves having you appear to be slightly off balance, and I realize you can’t hold that pose. I need to get the effect just right. And I think it will help if you have something to bang your fists against. Don’t worry—the glass is unbreakable.”

“Okay. Sure.” That made sense. Well, not really. But I’d stopped trying to understand everything he was doing, and I’d really started to enjoy the way the money piled up. Besides, it would definitely be easier posing, now that I had something to lean against. I stepped inside the box. “When is the painting due?”

Caspar closed the box. I heard something click. Then he said, “Oh, the final piece isn’t a painting.”

“No? What is it?”

“A sculpture,” he said. He bent over and picked up a hose from the floor. He attached the hose to the bottom of the box.

“Cool.” That could take weeks. The money would keep piling up. I looked around, but didn’t see a big block of stone. Maybe he was going to use clay. “Are you carving it?”

“No. I’m casting it,” he said. “Hold still.”

I noticed a suitcase and a couple boxes stacked in the corner. As I wondered whether he was moving to another studio, I felt something wet against my legs. A thick liquid was flooding the container.

“Hey! Stop that!” I banged my fists against the glass. It didn’t break.

In seconds, the liquid was up past my waist. It smelled like melted plastic. My phone had already gotten soaked. The fumes made my head spin. I banged my fists against the glass again. “Let me out!”

“Yes, perfect!” Caspar said. “Show your rage.”

The liquid was up to my chin. Then it flowed over my head. I realized he was planning to use my body as a mold for his sculpture.

I tried to smash the glass, but the liquid was so thick, I couldn’t build up any force. I couldn’t even move my legs. Whatever this stuff was, it had already turned solid down there. A moment later, my fists were frozen in place against the glass. On the other side, through a blur of glass and plastic, I could see Caspar’s fists clenched in triumph.

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo

Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus

Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus Emperor of the Universe

Emperor of the Universe Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool

Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets

Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy

Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy Numbed!

Numbed! Punished!

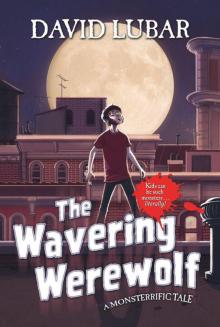

Punished! The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales)

The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales) Dog Days

Dog Days Sophomores and Other Oxymorons

Sophomores and Other Oxymorons The Psychozone

The Psychozone My Rotten Life

My Rotten Life Invasion of the Road Weenies

Invasion of the Road Weenies In the Land of the Lawn Weenies

In the Land of the Lawn Weenies Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies

Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies Ghost Attack

Ghost Attack Check Out the Library Weenies

Check Out the Library Weenies Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book)

Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book) Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories

Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories Hyde and Shriek

Hyde and Shriek The Wavering Werewolf

The Wavering Werewolf Dead Guy Spy

Dead Guy Spy Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies

Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies The Big Stink

The Big Stink The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies

The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies Character, Driven

Character, Driven The Bully Bug

The Bully Bug Beware the Ninja Weenies

Beware the Ninja Weenies Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge

Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge The Unwilling Witch

The Unwilling Witch Goop Soup

Goop Soup Lay-ups and Long Shots

Lay-ups and Long Shots The Gloomy Ghost

The Gloomy Ghost Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie

Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories

Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories Attack of the Vampire Weenies

Attack of the Vampire Weenies Enter the Zombie

Enter the Zombie The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale

The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale The Curse of the Campfire Weenies

The Curse of the Campfire Weenies The Vanishing Vampire

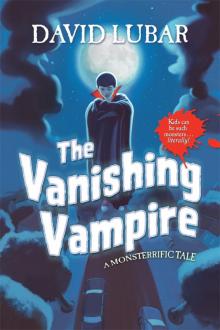

The Vanishing Vampire