- Home

- David Lubar

Character, Driven Page 8

Character, Driven Read online

Page 8

“Sure,” he said. “As long as you aren’t a hater. I don’t help homophobes.”

“I’m a dying-alone-and-unlaid-phobe,” I said. “That really terrifies me.”

“Hang in there and keep trying,” he said. “You’re kind of good-looking, in a nerdy, awkward way. Sometimes it takes girls longer to notice guys who aren’t flashy or dangerous. But they’ll catch on to you eventually. Hot girls like to chase wolves. But then they marry collies. Smart, loyal, pretty.”

“Uh, thanks…”

“Oh, and one more thing. You might want to find better ways to describe romantic encounters. ‘Getting laid’ makes it sound like you just want to use this girl as a moist substitute for your hand. She’s not just an object, is she?”

“No,” I said. “She’s awesome. She’s amazing.” I’d never considered myself to be crude, like the Thug Nuts, or a jerk about girls, but I guess he had a point. I really did sound like a sexist idiot when I talked that way. Damn, another thing to watch out for. Life was like a minefield of words.

Over the next half hour, Nicky showed me everything I needed for a workout routine. He explained how to balance exercise and rest, and the difference between bodybuilding and weight lifting. He could have taught a class at an upscale gym if he wanted. That’s how much he knew.

“Good job,” he said as I was walking out, exhausted but strangely content. Then he smacked me on the butt.

I let out an involuntary shout, but he laughed and said, “That was a manly smack. Don’t worry. You haven’t been molested, infected, or indoctrinated. Unfortunately, you’re still pathetically straight.”

“Thanks for helping me,” I said. “Hey, do you like Mack and Mary?” I figured the tickets were probably still on Ms. Ryder’s desk.

“Mack’s cute,” he said. “But their music sucks. Why?”

“No reason.” It had been worth a try.

On the way out, I found myself thinking that if I were gay, I would have been all over Nicky at the words “good-looking.” I mean, he was more than good-looking, himself. He had the sort of face you’d see in a commercial for macho stuff like chain saws or Ford trucks. His body was magnificent. But not in a way that attracted me. I couldn’t picture myself in a physical relationship with him. I was definitely straight.

I paused in the hall to look at myself in the mirrored back of the trophy case. Good-looking? Who knows? How could I expect to judge my own face? Especially now, when it was flushed and sweaty from exercise.

But I loved the feel of my shirt sticking to my body. It was pasted there with honest sweat. The last time I’d felt like this was back in July, when I did yard work around the neighborhood to make extra money.

After I got home and showered, even though I knew every muscle in my body was working furiously at becoming buff, I still didn’t feel great about myself socially. But an idea hit me as I was staring at my right arm, wondering how long it would take for the muscle growth to become evident.

I decided to give myself a tattoo.

I checked the Internet. It seemed like it was reasonably easy to tattoo yourself. That would be an immediate change, far faster than muscle growth, and one I could hold in my mind like an amulet as I walked through the halls at school. I wasn’t planning to make some sort of giant Asian carp or American eagle on my biceps, but I thought it would be cool to have something only I knew about. Maybe a quote. That’s what Butch had on her arm and on her ankle. I thought about some of the ones I liked.

Don’t let the bastards grind you down.

I don’t do drug. I am drugs.

Please, may I have more?

And so it goes.

I liked that last one. And not just because it was the shortest. It was a line that appeared throughout Slaughterhouse-Five. Vonnegut. Hah. I just realized that if I put those words on my stomach, I’d have a Vonne-gut.

Where to place my statement? My forearm would be the easiest. But it wouldn’t exactly be hidden there. I totally couldn’t let my parents ever see it. Dad would definitely hit a wall or two if he spotted me with a tattoo.

My leg.

That would work. I’d place it right at the top of my upper thigh, below my pelvis. A place where nobody would ever see the tattoo unless I wanted them to. It would also be easy to reach.

I got out a marking pen and sketched the words. AND SO IT GOES. I kept them fairly small. Four words. Eleven letters. Three spaces. Not that I’d have to put ink in the spaces.

I pulled together everything I needed, and got started. In the interest of not contributing to anyone else’s rash decisions, I won’t detail the equipment or methods. It’s better to let the Internet get all the blame if you decide to follow my example.

As I got ready to start, I realized that every puncture I made for the first letter of the quote would, literally, be an A-hole. I also realized I was stalling. I took three slow, deep breaths, steadied my hand, and plunged in.

The process hurt more than I expected. I almost stopped in the middle of the A. Actually, it stung more than it hurt. But I gritted my teeth, finished the first letter, and got started on the second.

This is a bad idea.

My mind hurled various unhelpful images at me. I pictured my leg getting infected. I pictured it getting amputated. I pictured the infection spreading to my groin. I pictured pustules of bubonic plague proportion erupting in my crotch like zombie testicles.

Despite those horrifying images, I kept going. After I finished the tattoo, I cleaned off my leg and regarded my handiwork. It was only at that point—as I was rereading the words I’d permanently injected into my flesh, admiring my skill in both the art of tattooing and the art of calligraphy, and contemplating these disciplines as possible career options—that I realized my mistake.

Picture this.

I was looking down at my upper leg, reading the words, AND SO IT GOES. From above, left to right. Reading with no effort. Looking down.

At upside-down words.

I could read my tattoo as easily as words on a street sign or a sentence in a book. But for the rest of the world, it was inverted. And so it went—upside down.

Damn. All that work, all that pain, and I’d screwed up.

On the bright side, there was no danger of embarrassment, since the way things were going in my social life, nobody else would ever see my mistake.

Inverted. Introverted. Everything is connected.

Maybe Kurt Vonnegut was looking down at me from heaven, reading my homage to him, and laughing his ass off.

Do people in heaven have asses?

Lumber Jerks

DESPITE THE INVERTED nature of my tattoo, I did feel like I was walking a bit taller the next day. Counterbalancing that, I was also walking a bit hunched over, thanks to the exercise-induced pain in my core muscles. But it was a good pain. I promised myself I’d lift again in a day or two, as soon as I was sure I could raise a barbell without screaming.

Third period, I showed the finished painting to Ms. Gickley. “If I work on it any longer, I think I’ll start scraping off paint,” I said. “Whether it’s good enough or not, I think I’m done.”

“Honestly, I wasn’t concerned how this one came out,” she said.

“Seriously?”

She nodded. I waited, knowing there was more.

“I wanted you to take your time. And you did. Right?”

“Right.” Because Mr. Yuler totally trashed me with one word.

“So you’ve proved to yourself that you can put more time into a painting. And, more important, you know how it feels to go slowly. Does that make sense?”

“Yeah. It does. Thanks.” I guess she was right. I’d had time to think as I worked. Until now, I’d always raced to finish each piece, eager to start the next one. It was like when I was eating dinner but thinking about dessert. Whether in the Art House or the weight room, it looked like this was my week to get taught. I liked that.

As I was about to walk away, I realized my ego still hadn’

t gotten the meal it had been hoping for. Or even a snack. “So, is it any good?”

“To me, it’s better than your first painting. And that’s good. It’s also better than it was last week. You improved it. And that’s great.”

I thanked her again, then went back to the main building to get a frame. As I approached the shop class, I heard banging, like someone was moving wood around in the supply closet. And I heard laughter. But it wasn’t the sort of laughter that made me feel good. It was the sort of laughter that carved a deep slash along my spine with a blunt chisel.

I was still ten or fifteen feet from the door, just close enough to catch the faint resin scent of sawed pine, when I heard a cluster of footsteps. I held the painting in front of my face, pretending to study it as I slowed my walk. I already knew, from their voices and their braying laughter, that it was Clovis and three or four other Thug Nuts who were about to emerge from the room. I didn’t know what they’d been doing in the woodshop, but I decided I was better off remaining ignorant. As they passed me, I gripped the painting harder, expecting one of them to knock it from my hands. They generally seemed to respond to anything of worth or beauty with violence and anger.

But they zipped right by, as if they were eager to get away from the scene of a crime. I waited until they’d moved out of sight, then headed back to the Art House, frameless but intact.

I brought the painting home after school.

“What’s that?” Dad asked from the living room couch, where he was watching an old movie.

I didn’t feel like going through a replay of Mr. Yuler’s art criticism. “Nothing.”

Dad twirled his index finger like he was stirring a cocktail with it. I turned the painting around and held it up.

He squinted at it for a moment. “That’s art?”

“Yeah.”

“Is it any good?”

“I don’t know.”

“That makes two of us.” He hit me with a snarky smirk, then turned back to the newspaper. It was obvious he was finished with our father–son moment.

That, at least, had been less brutal than Mr. Yuler’s reaction. Though, in some ways, it had also been more painful.

I put the painting in my room and went outside to do my homework. I would have liked to go into town for a change, just to get a bit farther away from the source of the sting, but I really didn’t have time.

There’s a square at the center of Rismore. We call it “the Green.” It’s pretty large, maybe as long on each side as two city blocks, flanked across the street on all four sides by stores, some offices, the post office, and a church. There was a movie theater on the Main Street side when I was a kid, but that closed up years ago, after a Cinema Twelve and a Cinema Sixteen opened up on highways at either end of town. A large walkway cuts through the middle of the Green, running east to west. There are also some smaller diagonal paths, dotted with benches. The rest of the area is grass, along with a scattering of oak trees and one lonely, twisted evergreen. The skaters, goths, punks, and other groups hang out in clusters in the south half, which is bordered by Jefferson Avenue. Random members bounce from group to group, like electrons in an ionic bond. The north belongs to thugs of various flavors. This arrangement bears absolutely no metaphorical connection to any other geographic north/south political divisions, either historical or contemporary.

If I had time to go to the Green, I’d be in the south. But I was rarely able to do that. It was about a fifteen-minute walk to town from my house. That’s why I usually ended up in the backyard. It got me outside and didn’t eat up a half hour during the round trip.

* * *

“CLIFF IS REMBRANDT,” Dad said as I was setting the table for dinner.

Mom looked at me.

“I brought home a new painting,” I said. “It’s no big deal.”

Her face lit up. “Let me see!”

Great. She’d be disappointed. But I knew there was no way I could talk her out of seeing the painting, so I got it from my room and brought it downstairs.

Mom gasped when I held it up. “Cliff! That’s brilliant!” She snatched the painting from my hands and cradled it as if it were the newborn Christ Child, dropped straight into her waiting arms by the Angel Guggenheim, and not a blurry crucifixion on a blurry game controller, overseen by a blurry eye in the sky. “We need to get this framed.”

“You like it?” After being smacked down repeatedly by artless critics, I wasn’t ready to allow too much room for hope.

“So bold,” she said. “So assertive, and yet subtle. It has the powerful impact of a work by Goya or Chagall.”

“Uh, thanks,” I said. That was high praise. I glanced at Dad, who seemed annoyed that Mom found any value in my efforts, then turned my attention back to her, though what I said next was for Dad’s benefit. “I can get a frame from woodshop. It won’t cost anything.”

“Your work overflows with ideas,” she said. “You obviously put a lot of thought into the symbolism.”

She said more, showering me with compliments and comparing me to at least a half dozen famous artists beside Goya and Chagall. At the mention of some of the names, I heard Dad mutter, “Died broke,” “Died crazy,” or other inspiring biographical tidbits. All he seemed to know about artists was their failures.

Eventually, I managed to pry the canvas from Mom’s grip. She wanted to hang it in the living room immediately. I convinced her that I still needed to make a couple small changes and go back for a frame.

As I was walking away, she said, “And I love the rose. It reminds me of the trivet you made in third grade. Do you remember that?”

“Sort of,” I said.

After dinner, when Mom headed upstairs to go to sleep and I headed out the door for a short shift at Moo Fish, Dad stopped me with a hand on the shoulder.

“I’ve spent most of my working life doing taxes for people,” he said.

“I know.”

“Do you know how many artists I’ve done taxes for?”

I shook my head. There didn’t seem to be any benefit in making a guess.

“None,” Dad said. “Nil. Zip. Squat. Artists don’t earn a living. They sponge off society. They live off food stamps or government grants funded by taxpayers. If that’s your plan, if your dream is to be a parasite, keep painting. But don’t plan on painting here.”

* * *

LATER, AS I was mixing up a five-gallon batch of Moo Fish’s secret tartar sauce (mayonnaise, hot dog relish, and paprika), I thought about those words. It seemed like a pretty big hint I might need to put “find an apartment” a lot higher up on my list of things to do next year.

Friday morning, I was even sorer from weight lifting. My initial enthusiasm had faded somewhat. I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to keep up the exercise. This whole “no pain, no gain” attitude seemed to run counter to pretty much any philosophy I could imagine adopting.

No pain, no problem. That was more my style.

At least I didn’t have gym class. It was a library day. I grabbed my usual spot at the computers between Butch and Robert.

“Watch this,” Robert said. He typed “astounding breasts” into the search window, then clicked on one of the results on the first page, which linked to a site whose name I won’t mention, because it was much closer to being sick than clever.

“That won’t work,” I said as the content filter’s message popped up, announcing that the site was screened and unavailable. I cast a nervous glance toward the librarian, Mrs. Yalza, who was busy laminating a READ poster.

Robert held up a finger. “Patience. That’s just step one.” He tapped the bottom of the message, by the name of the filtering program: Censor Senser. Then he went to Google and typed “How do I get around Censor Senser?”

A bunch of hits popped up. I was impressed. Even more impressive, those pages didn’t appear to be screened.

“I love the Internet,” Robert said.

I shifted to a different computer, on the other side of Butch, w

ho was deeply enough involved in whatever she was researching that she wasn’t paying any attention to Robert. I figured my body was already 98 percent stiff. I didn’t want to remain within sight of Robert’s monitor and make it a perfect 100. Besides, like anyone else over the age of ten, I could find porn without any help whenever I wanted to. And even when I didn’t want to.

But I realized that, for Robert, the thrill wasn’t in going to some sleazy website loaded with artificially inflated breasts; it was in beating the system. And, even better, in using the system to beat itself. He was more enthralled with silicon than silicone.

Despite feeling like a ninety-year-old man with arthritis, I made it through the rest of the school day, all the way to Government. I was definitely enjoying Ms. Ryder’s idea of civics a lot more than Mr. Tippler’s. She didn’t yell. And she wasn’t boring. Odds are, she’d probably never go ballistic and take her anger out on an innocent mirror, either. I could not picture her staggering drunkenly around a bar, or anywhere else. She was smiling and humming when I came in. I guess she appreciated getting the concert tickets. I saw she’d written a message on the board: Thank you very much! (You know who I mean.)

“You’re welcome,” I whispered.

So there I sat, enjoying the bittersweet knowledge that I was a secret benefactor, when I heard the siren. It’s never good when an ambulance comes racing toward the school. Especially when it cuts right across the lawn and keeps going, all the way up to the main entrance. Everyone rushed to the windows. Ms. Ryder didn’t stop us. The ambulance was followed by a hook-and-ladder fire truck and two police cars, though all three of those vehicles stayed at the curb.

“Should we get out of here?” Abbie asked. “There might be a fire.”

Ms. Ryder sniffed the air. “I don’t smell any smoke. And they’d pull the alarm if they wanted us out of the building.”

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo

Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus

Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus Emperor of the Universe

Emperor of the Universe Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool

Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets

Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy

Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy Numbed!

Numbed! Punished!

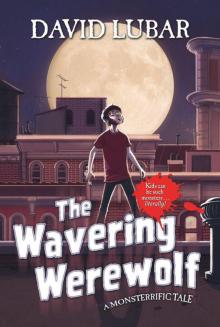

Punished! The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales)

The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales) Dog Days

Dog Days Sophomores and Other Oxymorons

Sophomores and Other Oxymorons The Psychozone

The Psychozone My Rotten Life

My Rotten Life Invasion of the Road Weenies

Invasion of the Road Weenies In the Land of the Lawn Weenies

In the Land of the Lawn Weenies Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies

Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies Ghost Attack

Ghost Attack Check Out the Library Weenies

Check Out the Library Weenies Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book)

Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book) Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories

Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories Hyde and Shriek

Hyde and Shriek The Wavering Werewolf

The Wavering Werewolf Dead Guy Spy

Dead Guy Spy Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies

Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies The Big Stink

The Big Stink The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies

The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies Character, Driven

Character, Driven The Bully Bug

The Bully Bug Beware the Ninja Weenies

Beware the Ninja Weenies Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge

Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge The Unwilling Witch

The Unwilling Witch Goop Soup

Goop Soup Lay-ups and Long Shots

Lay-ups and Long Shots The Gloomy Ghost

The Gloomy Ghost Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie

Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories

Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories Attack of the Vampire Weenies

Attack of the Vampire Weenies Enter the Zombie

Enter the Zombie The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale

The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale The Curse of the Campfire Weenies

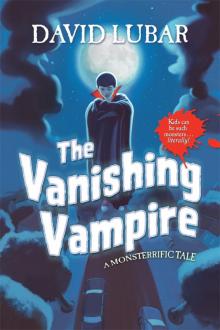

The Curse of the Campfire Weenies The Vanishing Vampire

The Vanishing Vampire