- Home

- David Lubar

Check Out the Library Weenies Page 16

Check Out the Library Weenies Read online

Page 16

And now, because some stories aren’t meant to be short, I invite you to turn to page 218 to enjoy a small sample of a new novel I am very excited about.

READING AND ACTIVITY GUIDE

Check Out the Library Weenies: And Other Warped and Creepy Tales

Ages 9–12; Grades 4–7

ABOUT THIS GUIDE

The questions and activities that follow are intended to enhance your reading of Check Out the Library Weenies, the ninth book in David Lubar’s popular anthology series. This guide has been developed in alignment with the Common Core State Standards. However please feel free to adapt this content to suit the needs and interests of your students or reading group participants.

WRITING AND RESEARCH ACTIVITIES

I. Short, But Not Always Sweet, Stories

A. David Lubar is a modern master of the short-story genre, especially tales that feature dark humor, twists and turns. Go to the library or online to develop a list of other authors of short stories or poems, from famous dark-tale teller Edgar Allan Poe to more contemporary writers. Select one author to research further. Use the information you gather to put together an oral presentation, describing the author’s most famous, or popular, works, story inspirations, writing process, and some of the most common themes and literary devices that appear in the works. Present your findings to friends or classmates. In small groups, discuss the similarities and differences among the short-story authors covered in the presentations. As you’re reading Check Out the Library Weenies, consider how the stories in this anthology follow, or break out of, patterns you identified in researching and discussing the short-story genre. (If you’ve read other Weenies anthologies, you might also consider how this volume is similar to, or different from, its predecessors.)

B. Many of the stories in Check Out the Library Weenies take unexpected twists and turns. There’s usually a “tipping-point” moment, when things escalate into the story’s core problem, or catastrophe. For example, the line from “Mummy Misses You”: “The trouble began when we went to the Ancient Civilizations wing.” As you read stories from this anthology, make a list of tipping, or turning, points. Think about the kind of language that “signals” this moment, or realization, for the main character. When you are done reading the stories and recording tipping points, review your list. Which tipping-point moment is (or moments are) the most effective, and why? Explain your answer in a short essay. Be sure to include relevant quotes and references from the stories to support your opinion.

II. From Head to Tale: Bringing Your Wildest Themes to Life

A. A special feature of David Lubar’s Weenies anthologies is the story notes he includes, which offer readers (and aspiring writers) insights into his writing process and inspirations. In his story notes for “Black Friday,” David Lubar says, “You can get endless story ideas by combining two concepts.” For example, he is intrigued by considering where vampires might hunt their human prey, as well as the cultural phenomenon of frenzied shopping on the Friday after Thanksgiving, which kicks off the holiday season in retail, but it is the intersection of those two ideas that drives the tale. Brainstorm a list of concepts that are of interest to you, then write a two to four-page short story that combines two of the ideas from your list. Consider making it a scary, or fantasy, story in keeping with the spirit of most of the stories in this collection.

B. David Lubar treats a wide range of subjects and themes in the Check Out the Library Weenies collection, including monsters, technology gone awry, time travel, unusual powers and opportunities, urban legends, and bullies, to name a few. Can you list some other themes David Lubar explores in this anthology? List each theme as a column head on a chart or spreadsheet. As you read, list each story title in the relevant column(s). Some of the themes are intrinsically scary or fascinating; other themes aren’t wild in and of themselves, but David Lubar approaches them with twists, turns, and techniques that make them unique and impactful tales. As you build, or review, the chart, highlight the themes, and note the treatments, that interest you most as a reader or writer.

C. Commenting on his “Rumplecodespin” story, David Lubar notes that, “Fairy tales make a great starting point for getting story ideas.” Pick a favorite fairy tale (or review fairy tale collections online or at the library, for inspiration). If desired, write a two- to four-page story that treats a modern-day scenario in that fairy tale’s framework. As Lubar did with his story title of “Rumplecodespin,” try to come up with a title that draws on the original fairy tale title, but gives it a humorous, modern spin.

D. David Lubar cites “What if…” questions as great inspiration for his stories. (He maintains an extensive file of “What if…” questions, which might offer unique jumping-off points for his short stories.) He also notes that school can be a rich source of story ideas. Discuss with friends or classmates something that you learned, or experienced, at school. Then brainstorm dark twists that could turn your personal anecdote into a great short story. Write a short story in which you apply one of the “twists” to your anecdote. As you’re writing, keep in mind the features that make the stories in the Check Out the Library Weenies anthology so compelling. Does your story use humor (dark or otherwise), hyperbole, or irony to make a point? Is the twist truly unexpected? Are the stakes for the main character high enough? Consider drafting a letter to author David Lubar, making the case why your story could hold its own in Weenie World.

E. However complex or clever the literary devices, sources of inspiration, plot twists, or themes may be, the short-story format requires the author to “get to the heart of the matter” quickly. The author must establish character, setting, mood, tone, theme, and the story’s pivotal conflict or problem in a limited amount of narrative time and space. David Lubar is a master at doing this not just efficiently, but creatively. After reading stories from this collection, try your hand at writing three or four compelling introductions (perhaps 6–10 lines of text each) that draw the reader in, and also establish all the critical story elements. If desired, pick your favorite paragraph, or “story start,” and develop it into a short story.

III. Scary and Literary: The Art (and Craft) of the Matter

A. Research these literary concepts and devices online or at the library:

pun; homonymic pun; connotation versus denotation; situational irony; poetic justice; point of view (including first person and third person and related variations); adage/aphorism/saying/cliché. List examples of stories from the Check Out the Library Weenies collection that illustrate or employ some of these devices. In pairs, or small groups, discuss how and why different literary devices (or combinations of devices) shape and drive your favorite stories from the collection.

B. “My Family History” is told from an animal (specifically a killer lizard’s) perspective; “Watch Your Grammar” borrows its format from the minutes of a school board meeting. What other interesting choices does David Lubar make in stories throughout this collection? Pick your favorite story from the collection, and write a one-page essay that identifies and describes the interesting choice David Lubar made in that story; consider some of the writing challenges that choice might have presented; and think about how he handled them, as evidenced by the successful end result.

C. Author David Lubar cleverly employs word play in his stories in an ingenious layered approach. The story “Death Comes Calling” is a great illustration of this layered word play, and the interplay of words’ denotations and connotations, or literal and figurative meanings. In “Death Comes Calling,” the character of Death needs someone to fix his cellphone (which itself is a device used for making calls), but the author also uses the phrase “comes calling” (an old-fashioned phrase for someone coming for a visit), as well as making a phone call (the “warning call,” which the victim ironically misses) the vehicle for someone’s death. Inspired by “Death Comes Calling,” and other cleverly layered titles in the collection, think of a pun, cliché, or popular expression, such as “A Steep

Learning Curve,” for example. What happens if you interpret it literally in a story? Brainstorm some possible phrases or words, and outline ideas for developing a story around it. If desired, write the short story.

D. Another story that plays with multiple meanings for the same word is “Watch Your Grammar,” where a school experiments with giving students Grammar Watches, which give kids a small electrical shock if they make grammatical errors in their speech. David Lubar plays with the different meanings of the word “watch”—to keep an eye on, as well as an actual wristwatch—in the story’s title and concept. In the story, the school decides it will explore other inventions like Posture Belts and Positive Thinking Helmets to help keep their middle school students on track. After you read the story “Watch Your Grammar,” collaborate with a small group of friends or classmates to brainstorm “inventions” to address irritating habits of grown-ups, a “Longwinded Shortcutter,” or whatnot. On posterboard, list name and function, and illustrate the invention. In groups, present and promote your products. Classmates can vote on best intervention invention. Use posterboard product proposals for a classroom or library display of “Intervention Inventions” inspired by David Lubar’s “Watch Your Grammar” story.

E. Regarding “The Sword in the Stew,” David Lubar writes: “And one of my favorite types of titles is those that play with well-known fables, classic stories, or fairy tales. In this case, The Sword in the Stone, which is the title of a classic book about King Arthur, led me to “The Sword in the Stew.” Do you have a favorite poem, story, or book you’ve read that would be fun to reimagine as, or use as the foundation for, a scary short story? What would you pick and why? Make a list of the key elements (title, main character, basic plot, and key theme) of the original work. In a second column, list how you’d change those elements to play with and transform it into your new story. What do you think might be challenging about this process?

Supports Common Core State Standards: W.4.1, 5.1, 6.1, 7.1; W.4.3, 5.3, 6.3, 7.3; SL.4.1, 5.1, 6.1, 7.1; SL.4.4, 5.4, 6.4, 7.4; RL.4.1-4, 5.1-4, 6.1-4, 7.1-4; RL.4.6, 5.6, 6.6, 7.6.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. In the story “How to Slay Vampires for Fun and Profit,” one vampire mocking main character Johann and his friends for being so easily tricked, says: “What fools these mortals be!” This quotes a line spoken by a character named Puck, a sprite who likes to play tricks on humans, from Shakespeare’s famous play A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Why do you think the author chooses to include the line in this story? How do some of the other stories in this collection illustrate, or explore, the idea of people facing harm, suffering, or even death, due to their own greed, ignorance, or selfishness?

2. How do the expressions “too good to be true,” “the joke’s on you,” or “be careful what you wish for,” apply to Johann in “How to Slay Vampires for Fun and Profit,” the twins in “Fairyland,” and the boys in “Searching for a Fart of Gold”? Are there other stories where you would say one or all of these phrases apply? Explain your answer.

3. In his story notes referring to “All That Glitters,” author David Lubar says he wanted to be sure the subgenre of “monster stories” was sufficiently represented in his anthology. How does including the element of monsters—in this case werewolves and vampires—“raise the stakes” (pun intended!) of a story? Why do you think the author chooses to have the werewolf approach another imaginary creature, a wizard, to facilitate his plan?

4. In tales like “Physics for Toons” and “Romeo, Romeo, Wherefloor Argle Roblio?”, trouble with technology causes some problematic outcomes. Do you think the author is commenting in these stories on the use, or over-use, or possible downside, of so much technology in youth culture today? Why or why not? Are there other stories in the collection you might categorize as “Tech Tales”? Which ones and why?

5. Many of the tales’ titles, including “Bald Truths” and “Off the Beaten Track,” to name just a couple of examples, incorporate wordplay, such as puns, or are a parody of a literary reference or popular saying or phrase. Many of the titles, like “Call Me” and “I Can’t Quite Put a Finger On It,” work on both figurative and literal levels, making a pun and a point at the same time. If you had to pick the story title that you thought was most clever in its use of language, which one would you pick and why? Explain your answer.

6. In his story notes about “Check Out the Library Weenies,” the anthology’s title tale, David Lubar writes: “I was worried about going against a structure I’d established. For the first eight books, the Weenies was someone mockable, like those joggers who never smiled, or the people who loved their lawns a little too much. In the case of Library Weenies, the Weenies would be the good guys.” If you have read other Weenies anthologies, how do you feel about this change? Is your reaction positive, negative, or neutral? Explain your answer. Check Out the Library Weenies celebrates the wealth of the mind, not just the wallet. It promotes the power and pleasure of reading, learning, science, intelligence, and invention; but it’s also a monster story, with a title that contains a pun (since you “check out” books from your library). So this tale exemplifies a lot of the unifying, or recurring, structural and thematic elements that inform this anthology. Can you think of other representative elements this signature story includes? Do you agree with the author’s choice to make this the title tale? Why or why not? If not, what tale would you pick, and why?

7. A lot of the Check Out the Library Weenies stories portray friend, sibling, kid/parent, or kid/teacher relationships, as well as scenarios with bullies, which involve middle-school-aged kids. Based on what you observe in your family, school, and community, do you think that middle school characters, attitudes, relationships, and dynamics are depicted accurately in these stories? Why or why not? Explain your answer, citing specific examples and stories from the anthology. Do the Check Out the Library Weenies stories include some examples of friendships where there is a good balance of power between friends or siblings? How does the author illustrate that?

8. Several of the stories in the collection, including “Come Back Soon,” “A Boy and His Frog,” and “2D or Not 2D,” involve characters having the power to manipulate nature, or even time or fate. Having such powers could be convenient, empowering, or even life-changing, but do you think the author is also inviting readers to think about the risks of using, or abusing, such powers? Explain your answer.

9. Urban legends are critical to “Gordie’s Gonna Git Ya” and “Ghost Dancer.” Does your school or community have any such legends? How, and why, do you think people keep such legends alive? In the same vein, why do you think readers enjoy scary stories?

10. The narrator in “At Stake” is excited about possessing the power to make anyone or anything “drop dead” by simply saying the words, but knows the power, which makes her different from, and a threat to, others can be a liability, too, saying: “But fear meant danger. We destroy the things we fear, if we get the chance. I’d have to watch my back.” Do you agree or disagree with the idea that people destroy things they fear? What other stories in this anthology raise this idea?

11. The story “Off the Beaten Track” features a “real-life monster,” a creepy man threatening to murder kids walking out by the train track. In his story notes, David Lubar says “I’m always a bit apprehensive when I use a story with a real-life monster rather than an imaginary creature. But I think my readers can handle this one.” Do you find this kind of story, or the stories with make-believe monsters, like werewolves or vampires, scarier? If you were the author or editor on this project, would you have chosen to include this story, or would you have left it out in favor of a fictitious monster story?

Supports Common Core State Standards: RL.4.1-4, 5.1-4, 6.1-4, 7.1-4; RL.4.6, 5.6, 6.6, 7.6; SL.4.1, 5.1, 6.1, 7.1; SL.4.4, 5.4, 6.4, 7.4.

Read on for a sneak peek of Da

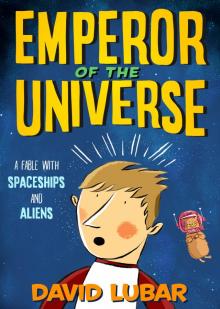

vid Lubar’s new novel, coming soon from Starscape

When seventh grader Nicholas V. Landrew, his beloved pet gerbil Henrietta, and a package of ground beef are beamed aboard an alien space ship, they soon find themselves on the run in a madcap chase across the universe.

Now all Nicholas wants to do is get back home before his parents find out and ground him forever, but with the Universal Police hot on his trail, that won’t be easy. Before it’s all over, Henrietta will find herself safely ensconced back in her cage, Nicholas will be crowned Emperor of the Universe, and something even more surprising will happen to the package of ground beef.

GONE IN A FLASH

Nicholas V. Landrew was not a typical ninth grader. That isn’t surprising. There is no typical ninth grader. Or tenth or eighth. Or teacher or parent. Or rodeo clown or oyster shucker, for that matter. But Nicholas was not far from what was considered normal by the social standards of his place and time, or the hypercritical judgment of his peers. He couldn’t shoot milk from the corner of his eye, like Nikolai C. Landrew of Oxnard, MI, dousing candles at ten feet, or memorize the serial number of a dollar bill on sight and extract the square root to seventeen decimal places, like Nicole D. Landrew of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. On the other hand, neither Nikolai nor Nicole would ever rule the universe, so we will not speak of them again.

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President

Teeny Weenies: My Favorite President Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo

Teeny Weenies: The Intergalactic Petting Zoo Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus

Teeny Weenies: The Eighth Octopus Emperor of the Universe

Emperor of the Universe Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool

Teeny Weenies: The Boy Who Cried Wool Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets

Teeny Weenies: Fishing for Pets Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy

Teeny Weenies: Freestyle Frenzy Numbed!

Numbed! Punished!

Punished! The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales)

The Wavering Werewolf: A Monsterrific Tale (Monsterrific Tales) Dog Days

Dog Days Sophomores and Other Oxymorons

Sophomores and Other Oxymorons The Psychozone

The Psychozone My Rotten Life

My Rotten Life Invasion of the Road Weenies

Invasion of the Road Weenies In the Land of the Lawn Weenies

In the Land of the Lawn Weenies Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies

Wipeout of the Wireless Weenies Ghost Attack

Ghost Attack Check Out the Library Weenies

Check Out the Library Weenies Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book)

Looniverse #1: Stranger Things (A Branches Book) Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories

Pulling up Stakes and Other Piercing Stories Hyde and Shriek

Hyde and Shriek The Wavering Werewolf

The Wavering Werewolf Dead Guy Spy

Dead Guy Spy Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies

Strikeout of the Bleacher Weenies The Big Stink

The Big Stink The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies

The Battle of the Red Hot Pepper Weenies Character, Driven

Character, Driven The Bully Bug

The Bully Bug Beware the Ninja Weenies

Beware the Ninja Weenies Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge

Extremities: Stories of Death, Murder, and Revenge The Unwilling Witch

The Unwilling Witch Goop Soup

Goop Soup Lay-ups and Long Shots

Lay-ups and Long Shots The Gloomy Ghost

The Gloomy Ghost Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie

Sleeping Freshmen Never Lie Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories

Zero Tolerance Meets the Alien Death Ray and Other (Mostly) Inappropriate Stories Attack of the Vampire Weenies

Attack of the Vampire Weenies Enter the Zombie

Enter the Zombie The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale

The Wavering Werewolf_A Monsterrific Tale The Curse of the Campfire Weenies

The Curse of the Campfire Weenies The Vanishing Vampire

The Vanishing Vampire